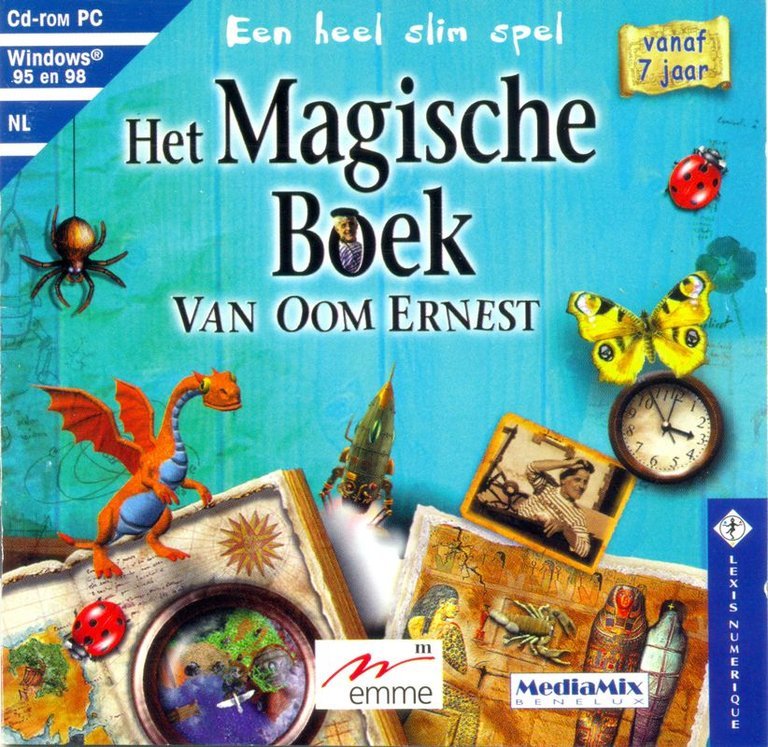

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: EMME Interactive SA, VTechSoft Inc.

- Developer: Lexis Numérique SA

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Item manipulation, Non-linear, Puzzle

- Setting: Book, Fantasy

Description

Uncle Albert’s Magical Album is a first-person adventure puzzle game where players explore the magical pages of a book in Uncle Albert’s attic, solving non-linear puzzles to reveal the titular character’s secrets and free the trapped chameleon, Tom. Aimed at children aged 7 and up, the gameplay involves dragging items and animals across pages, using tools like a camera and watering can, with randomized elements for varied experiences that blend science and fantasy.

Gameplay Videos

Uncle Albert’s Magical Album Free Download

Uncle Albert’s Magical Album Guides & Walkthroughs

Uncle Albert’s Magical Album: A Timeless Journey Through a Living Chronicle of Wonder

In the crowded landscape of late-1990s educational software, where titles often struggled to balance pedagogy with engagement, Uncle Albert’s Magical Album (originally L’Album Secret de l’Oncle Ernest) emerged not as a mere teaching tool, but as a genuine artifact of digital childhood wonder. Released in 1998 by the French studio Lexis Numérique, this first entry in the Uncle Albert’s Adventures series defied its “ages 7 and up” label to create an experience that resonated deeply with players of all ages, earning near-universal critical acclaim and enduring cult status. This review will argue that Uncle Albert’s Magical Album is a masterclass in interactive world-building and elegant puzzle design, whose significance lies not in groundbreaking technology, but in its profound understanding of the simple, profound joy of discovery—a quality that has allowed it to transcend its era and educational genre trappings to become a cherished piece of video game history.

Development History & Context: The Alchemy of French Creativity and TechnologicalConstraint

The game was born from the mind of Éric Viennot, whose roles as original idea creator, scenario writer, and art director underscore the deeply personal, auteur-driven vision behind the project. Developed by Lexis Numérique SA and published by Emme Interactive (with VTechSoft handling the US release), the title was built using the mTropolis multimedia authoring engine—a common but limiting tool for CD-ROM adventures of the period. This technological context is crucial: mTropolis was not a bespoke game engine but a generalized environment for creating interactive presentations, which imposed significant constraints on performance, graphical fidelity, and complex interactivity.

Yet, within these constraints, the team—comprising 39 credited developers across art, sound, programming, and QA—practiced a form of creative alchemy. The development history, illuminated by a pre-release trailer and unused assets, reveals an iterative process focused on polishing a unique core concept. Early versions show a clunkier interface (an initially upside-down camera tool, a different bottom toolbar with a missing hammer, different bookmark designs) and less refined puzzle elements (a giant sarcophagus shell, flies not yet contained in a matchbox). The final version’s streamlined approach—where tools like gloves are used intuitively without explicit mode-switching and the interface facilitates seamless item dragging across “pages”—speaks to a development philosophy prioritizing player intuition and atmospheric immersion over technical showmanship. This was a game made with the CD-ROM’s capacity for rich audio-visual assets in mind, not for pushing polygon counts.

The gaming landscape of 1998 was dominated by the 3D acceleration race and gritty narratives, but a niche for high-quality, non-violent educational and adventure software persisted, particularly in Europe. Titles like the Playtoons series or Dracula’s Secret (both mentioned as related) occupied a similar space, but Uncle Albert distinguished itself through its cohesive, book-based diegesis. It arrived at a moment when the adventure genre was seeking new metaphors beyond the traditional point-and-click room, and it found one in the tactile, page-turning experience of a personal journal—a format that inherently suggested non-linearity and curated discovery.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Gentleman Scholar’s Legacy

The narrative is deceptively simple, serving primarily as a framing device for the gameplay, yet it isthis framing that generates the game’s thematic resonance. The player inherits access to the “Secret Album” of Uncle Albert, a globe-trotting inventor and scholar whose attic-bound book is a magical repository of his travels. The ostensible goal is to “reveal the secret of Uncle Albert,” but the true narrative emerges from the act of exploration itself.

Uncle Albert is a quintessential Jules Verne or Franco-Belgian comic protagonist: a figure of boundless curiosity, gentlemanly eccentricity, and practical ingenuity. He is never seen, only heard through periodic, warm voice recordings on a tape recorder—a clever device that maintains his mysterious, off-screen presence while providing direct, pedagogical guidance. His voice (provided by Jean-Pascal Vielfaure, who also handled sonorisation) is the game’s constant companion, a reassuring and witty authority that frames each puzzle not as a chore, but as an invitation to see the world through an inventor’s eyes.

The thematic core is applied curiosity. Every page of the album is a vignette from Albert’s life—a laboratory, an Egyptian pyramid, a desert, a space station—each populated with living animals and dormant mechanisms. The player, aided by the chameleon Tom (the game’s closest thing to a protagonist), is not a hero fighting antagonists but an apprentice deciphering a master’s notes. The puzzles arelogical extensions of the environments: using fire to scare animals, water to coax a snail from its shell, a jackhammer to break stone. This creates a thematic unity where problem-solving is the story. The “secret” at the album’s heart is less a plot twist and more a metaphor for the accumulated wisdom and wonder of a life spent exploring—the ultimate revelation being the player’s own activated sense of wonder.

The non-linear structure is narratively justified: the album’s pages can be visited in any order, reflecting how a real journal or scrapbook is not a linear story but a collection of memories and curiosities. Unlocking new pages as tools are found mirrors the expanding horizons of a developing mind. The inclusion of “crumpled pieces of paper” as hint-providers further deepens the diegesis, making them feel like Albert’s own hastily scrawled marginalia.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Elegance in Environmental Interaction

Uncle Albert’s Magical Album operates on a brilliantly simple yet profound core mechanic: inventory-based, cross-page environmental puzzle-solving. The entire game world is the open, two-dimensional spread of the album’s pages. The player navigates using a row of thematic bookmarks (e.g., “Frog,” “Pyramid,” “Treasure Island,” “Laboratory,” “Space Station”—33 in total, as listed in the wiki). Each bookmark leads to a distinct, self-contained “screen” or page.

The gameplay loop is as follows:

1. Select a bookmark/page.

2. Observe the scene, listen to Uncle Albert’s cryptic audio hint, and find any crumbled paper hints.

3. Identify the problem or task on that page (e.g., get the frog to jump to the lily pad, retrieve an object from a spiderweb).

4. Collect items (animals, tools, objects) from the current page or from previously solved pages.

5. Drag these items to logical points of interaction within the same page or onto other pages. For instance, you might catch a fly on the “Frog” page, carry it in your inventory (represented as a small icon), and use it on the spiderweb on the “Spiderweb” page.

6. Solve the puzzle, which often involves one of the five collectible tools: camera (to photograph clues), printer (to print maps or images), fire (to manipulate heat-sensitive elements or scare creatures), jackhammer (to break through barriers), and watering can (to interact with plant life or amphibians).

This system is revolutionary in its simplicity and its faithful simulation of the album metaphor. Items exist in persistent, page-bound space. Dragging a snail from the “Pond” page to the “Flowers” page feels like physically placing it in a different part of a real scrapbook. This eliminates the abstraction of a global inventory screen, grounding all interaction in the tangible, page-turnable world.

The non-linear progression is a masterpiece of design. The five essential tools are scattered across different bookmarks. The player must deduce which pages to visit to find the required tool for a given puzzle, creating a natural, self-directed exploration. The game uses “variables to randomize the gameplay with each game”—likely the starting positions of certain items or the solution to a minor puzzle—encouraging replayability and preventing rote memorization.

Support systems are integrated diegetically. The flute summoning Tom the chameleon for additional help is a perfect example: it’s an item you find, and using it brings the character to life on the current page to offer a hint, blending tool-use with narrative companionship. The tape recorder and crumpled papers provide tiered hints, allowing players of different skill levels to progress without breaking immersion.

Where the system could have been confusing is in its sheer breadth of possible interactions. But the game’s logic, while whimsical, is internally consistent and based on real-world (if fantastical) principles. As one critic noted, “experimentation is not only encouraged—it is essential.” The game trusts the player to think like an explorer, fostering a sense of intellectual agency rarely afforded in children’s software.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Hand-Drawn Dream of Infinite Possibility

The atmosphere of Uncle Albert’s Magical Album is its most celebrated and defining feature. The art direction, led by Éric Viennot with a team including Nicolas Delaye and Michel Aurousseau, creates a world that is simultaneously nostalgic, adventurous, and cozy. The visual style is a direct descendant of Jules Verne illustrations and Franco-Belgian comics (bandes dessinées), specifically evoking the detailed, cross-hatched, imaginative realism of artists like Albert Robida or the ligne claire clarity of Hergé, but infused with a playful, magical sensibility.

Each page is a lush, hand-drawn illustration, rendered in a warm, slightly muted color palette that feels like an old, cherished book. The 2D art provides the foundational scenes, while 3D art and special effects (by Nicolas Lembrouck, Stéphane Valette, etc.) are used sparingly but effectively for certain animated elements—the flickering flame, the rotating gears of a mechanism, the shimmering of a magic effect. This hybrid approach gives the world a tactile, layered quality. The “bookmark” tabs themselves are charming, illustrated icons that act as portals to these worlds.

The world-building is achieved through environmental storytelling alone. The “Laboratory” page is not just a puzzle; it’s a snapshot of a brilliant mind at work, with bubbling beakers, intricate blueprints, and strange apparatuses. The “Pyramid” and “Sarcophagus” pages convey ancient mystery, while the “Space Station” and “Rocket” pages channel retro-futurism. The game’s scope is genuinely global and fantastical, moving seamlessly from a humble garden to cosmic adventures, all contained within the same physical book. This creates a sense of boundless possibility—the attic book is a microcosm of the entire world of adventure.

The sound design is equally integral. Jean-Pascal Vielfaure and Frédéric Lerner’s original music is melodic, whimsical, and understated, often using playful woodwinds or gentle piano to underscore each location’s mood without overwhelming it. The voice recordings are a masterstroke. Uncle Albert’s narration—warm, slightly accented, laden with gentle humor and encouragement—provides the crucial human connection. He doesn’t dictate solutions but prods the player’s imagination: “Perhaps the frog would jump if you gave him something to eat?” The sound effects for interactions (a click, a splash, a mechanical whir) are crisp and satisfying, reinforcing the tactile feedback of manipulating the album.

Together, these elements create an atmosphere of innocent, intellectual wonder. It’s a world where a chameleon can be a friend, a watering can is a key, and every page holds a secret. This aesthetic and auditory cohesion is what allows the game to feel timeless, avoiding the dated CGI look that plagues many of its contemporaries.

Reception & Legacy: From Critical Darling to Cult Preservation

Upon its 1998 release in France (and 1999 in English-speaking territories), Uncle Albert’s Magical Album was met with near-universally rave reviews, as evidenced by the aggregated 98% score from critics on MobyGames. Da Gameboyz awarded a perfect 5/5, praising its “balanced blend of science and fantasy” and ability to capture “the innocence and wonder of childhood,” with the sole complaint being its brevity. Review Corner scored it 9.6/10, highlighting its endless possibilities, multiple solutions, and encouragement of experimentation: “Players are constantly discovering new things.”

Commercially, it was a significant success within its market. The Wikipedia entry notes that the first three games in the series sold a combined 500,000 units by October 2002, with the first game alone selling over 100,000 copies worldwide according to the Uncle Albert Wiki. It garnered prestigious awards in France and Europe, including the Prix Möbius 1998 and the Eurêka d’Or for Best CD-ROM of the Year, and was nominated for the Europrix, EMMA Awards, and Macworld Awards. It also won the New Media Prize at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, a crucial endorsement that situated it not just as a game, but as a form of interactive literature.

Its legacy is multifaceted. Within the educational and children’s software space, it set a high bar for integrating narrative, art, and puzzle-solving. It demonstrated that “edutainment” could prioritize engagement and aesthetic depth over dry instruction. The series continued with Uncle Albert’s Fabulous Voyage (2000) and Uncle Albert’s Mysterious Island (2001), both released in English, cementing its franchise status in Europe. However, it never achieved the mainstream breakthrough of contemporaries like Myst or The Secret of Monkey Island, remaining a beloved but niche treasure, particularly in its native France and among those who played it in childhood.

Today, its reputation has evolved into that of a cult classic and a preservation priority. Its inclusion on abandonware sites (MyAbandonware, Macintosh Garden) and its status as a frequent subject of GOG Dreamlist requests (with users passionately arguing for its re-release) are testaments to its enduring fanbase. The detailed wiki dedicated to it,plete with translation tables and development trivia, shows a community committed to documenting its history. The fact that it can still be played via emulation (SheepShaver for Mac, VirtualBox for Windows) and that modern users share configuration tips to bypass sound card issues, speaks to its resilient design.

Its influence is subtler than seismic, but discernible. It prefigured the “environmental puzzle” focus of later narrative adventures like Machinarium or Day of the Tentacle, where the joy comes from the logical poetry of using the world against itself. More directly, it stands as a high point in the short-lived but vibrant genre of the page-based, first-person interactive book, a vein later mined by titles like Drawn series or the narrative puzzles of The Book of Unwritten Tales. Its commitment to a single, cohesive, beautiful interface (the album itself) remains an inspired design choice rarely replicated.

Conclusion: An Indelible Page in the Anthology of Play

Uncle Albert’s Magical Album is not a game defined by technical prowess or narrative complexity. Its genius lies in its pure, unadulterated faith in the player’s desire to explore and understand. By anchoring its entire experience in the metaphor of a living, magical scrapbook, it created a space where every interaction felt meaningful, every page a new chapter in a personal adventure. The puzzles are clever but never cruel, the world is vast but never overwhelming, and the guiding presence of Uncle Albert provides just enough narrative glue to make the exploration feel purposeful.

From its constrained mTropolis foundations, Lexis Numérique crafted an experience of remarkable warmth and intelligence. Its critical adulation, commercial success in its target markets, and decades-long fan devotion are not accidents; they are the earned rewards of a design that respected its audience’s imagination. In the grand tapestry of video game history, it represents a vital strand: the poetic potential of the adventure-puzzle genre, the power of aesthetic cohesion, and the timeless appeal of a well-told, interactive mystery.

While it may be remembered by many as a simple childhood computer game, a deeper examination reveals Uncle Albert’s Magical Album to be a sophisticated, lovingly crafted artifact. It is a testament to the era of CD-ROM creativity and a perennial invitation to open a very special book. Its place in history is secure—not as a bestseller that changed the industry, but as a beloved, enduring classic that captured the magic of discovery and packaged it into a digital album, waiting for each new generation to turn its pages and uncover its secrets. It is, in the truest sense, an evergreen adventure.