- Release Year: 1980

- Platforms: Intellivision, Windows, Xbox 360

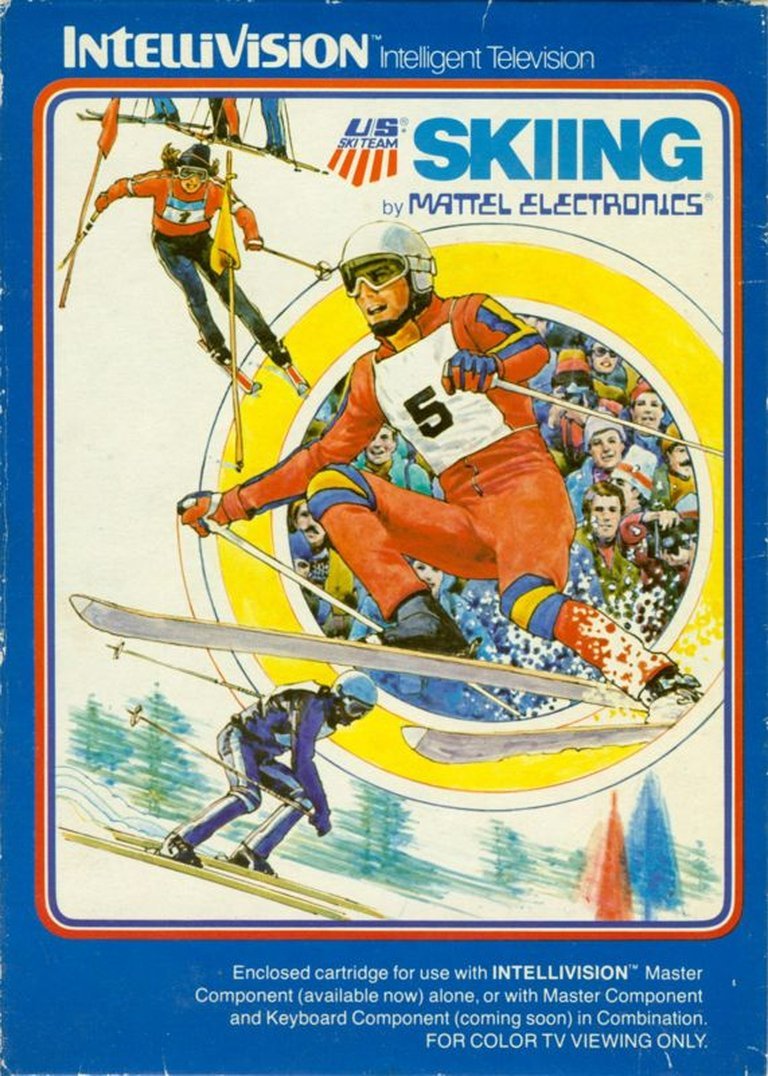

- Publisher: Mattel Electronics, Microsoft Corporation

- Developer: APh Technological Consulting

- Genre: Sports

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Downhill, Racing, Slalom

- Setting: Snow, Winter

- Average Score: 69/100

Description

US Ski Team Skiing is a 1980 sports game for the Intellivision where players race downhill through snowy slopes, avoiding trees and jumping over moguls across slalom and downhill courses. The game supports single-player time trials or turn-based multiplayer for up to 6 players competing over three heats, with adjustable slope grades and speed settings to customize difficulty.

Gameplay Videos

US Ski Team Skiing Guides & Walkthroughs

US Ski Team Skiing Reviews & Reception

intvfunhouse.com (67/100): We had a blast seeing how fast we could go and smash into trees.

mobygames.com (72/100): Hasn’t aged well. But back in 1980, was the cat’s meow.

US Ski Team Skiing: Review

Introduction

In the frosty dawn of home console gaming, when pixels were scarce and ambitions were bold, US Ski Team Skiing carved its niche as one of Mattel Electronics’ earliest licensed sports titles for the Intellivision. Released in December 1980 during the console wars’ nascent phase, this vertically scrolling skiing simulator offered a tantalizing glimpse of winter sports on the small screen. More than a mere technical demo, it embodied the era’s ethos of accessible multiplayer competition and licensed authenticity, leveraging the U.S. Ski Team’s brand cachet to lend credibility to its digital slopes. While its legacy is often overshadowed by Activision’s contemporaneous Skiing for the Atari 2600, the Intellivision iteration remains a fascinating artifact of early sports gaming—a testament to how hardware constraints and licensing ambitions collided to create both innovation and limitation.

Development History & Context

US Ski Team Skiing emerged from the fertile ground of Mattel Electronics’ ambition to position the Intellivision as a premier home entertainment system. Developed by APh Technological Consulting—a boutique studio helmed by programmer Scott Reynolds—the game was one of Mattel’s first forays into licensed sports, capitalizing on the 1980 Winter Olympics’ cultural momentum. Reynolds, whose credits spanned Major League Baseball and Auto Racing, brought a disciplined approach to coding, though a humorous anecdote reveals the studio’s irreverent side: years after release, a programmer discovered that all variables and subroutines in the source code were named with “vilest obscenities,” a cheeky rebellion against corporate rigor.

Technologically, the Intellivision’s unique hardware dictated design choices. Its 16×12 grid resolution and limited color palette (16 colors on-screen) forced Reynolds to craft a deceptively simple yet effective aesthetic. The controller’s signature 12-button keypad and disc were repurposed for intuitive skiing controls—a precursor to modern analog stick precision. The game was initially bundled with the Go For the Gold compilation (which never materialized due to Mattel’s 1984 collapse), underscoring its Olympic aspirations. Its release coincided with Atari’s Activision Skiing (December 1980), creating an unintentional rivalry. While Activision’s game focused on single-player mastery with procedurally generated courses, Mattel prioritized multiplayer accessibility, reflecting divergent philosophies: Activision for the purist, Mattel for the party.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

As a sports simulation, US Ski Team Skiing eschews traditional narrative in favor of competitive tension. The game’s “plot” is distilled to a simple objective: descend a mountain faster than rivals, avoiding obstacles and gate penalties. Thematically, it embodies the 1980s obsession with athletic achievement and Olympic ideals. The U.S. Ski Team license (used prominently in initial packaging and marketing) lent an aura of authenticity, positioning players as aspirational racers. This was a masterstroke of branding—transforming abstract joystick-waggling into a symbolic quest for sporting glory.

Characteristically, the game lacks named protagonists or antagonists. Instead, the “narrative” unfolds through gameplay: the tension of gate penalties, the catharsis of clearing a mogul jump, and the communal roar of the crowd at the finish line. The absence of story elements underscores the era’s focus on replayability over narrative depth. Yet, subtextually, the game mirrors the Cold War-era Olympic spirit—a microcosm of national pride in digital form. The multiplayer “hot seat” mechanic, where players take turns racing, amplifies this theme, turning living rooms into makeshift ski lodges where camaraderie and competition coexist.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

US Ski Team Skiing centers on two core modes—downhill and slalom—each demanding distinct strategies. Control is elegantly mapped to the Intellivision’s disc and buttons: the disc for gradual turns, one button for sharp pivots, and another for jumping over moguls. Skiers accelerate automatically based on selected steepness (15 levels from gentle to perilous), creating a physics-based rhythm where timing and precision matter most.

The slalom mode emphasizes gate navigation, with flags demanding precise weaving. Missing a gate incurs a strict five-second penalty, a mechanic that turns near-misses into heart-pounding moments. Downhill mode, by contrast, rewards speed and obstacle avoidance, with moguls acting as both hazards and opportunities for aerial maneuvers. Players can adjust game speed (four settings) and slope grade, adding replayability. The three-heat structure ensures consistency, while support for 1–6 players (via turn-based “hot seat”) positions it as a social centerpiece.

Yet, the game reveals its era’s constraints. A single course per mode limits variety, and the lack of collision physics reduces trees to static obstacles rather than dynamic threats. The five-second gate penalty feels punitive compared to later titles, and the absence of saveable high scores hampers long-term engagement. Still, these flaws are mitigated by the sheer satisfaction of mastering a run—a loop of trial, error, and incremental improvement that defined early gaming.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s visual design is a triumph of minimalist artistry. The mountain is rendered as a stark white void with sparse black trees, creating a striking contrast that emphasizes the skier’s vibrant form. Reynolds exploited the Intellivision’s hardware to render multi-colored skiers (a rarity for 1980), adding personality to otherwise abstract avatars. The vertically scrolling landscape creates an illusion of speed, with the screen’s descent mimicking gravity—a technical feat that predated true 3D engines.

Sound design is equally functional yet evocative. Minimalistic audio cues include a satisfying “thump” on mogul impacts and a sharp “whack” for tree collisions. The crown jewel is the finish-line crowd cheer—a nostalgic whistle that evokes Intellivision’s signature audio flair. While sparse, these sounds immerse players in the alpine atmosphere, turning the living room into a makeshift ski resort. The absence of music underscores the era’s technical limits but heightens the focus on gameplay feedback.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, US Ski Team Skiing garnered lukewarm but pragmatic praise. Video magazine deemed it “nothing breathtakingly new” but lauded its “amazing amount of detail in an easy-to-learn contest.” Critics noted the multiplayer mode was “equally entertaining” as single-player, though the limited course variety drew criticism. Contemporary players like BigM remembered it as “the cat’s meow” in 1980, acknowledging its visual proximity to Activision’s Skiing but lamenting its single-player focus.

Commercially, the game thrived through rebranding. Sears’ private-label “Super Video Arcade” version dropped the U.S. Ski Team branding, simplifying the title to Skiing. Its legacy blossomed post-1984 when INTV Corporation released Mountain Madness: Super Pro Skiing (1988)—an enhanced sequel with 32 courses, random generation, and player-designed slopes. This sequel, though niche, cemented the original as a foundation. Modern retrospectives highlight its historical significance: it pioneered vertical scrolling on Intellivision and licensed sports integration, influencing later titles like Cool Boarders (1997). Its inclusion in compilations like Intellivision Lives! and Microsoft’s Game Room ensures its survival as a playable artifact.

Conclusion

US Ski Team Skiing stands as a curious microcosm of early gaming ambition: a game constrained by hardware yet elevated by vision. It lacks the narrative depth of modern titles and the technical polish of Activision’s Skiing, but its multiplayer focus, licensed authenticity, and elegant simplicity make it a touchstone of the Intellivision library. Scott Reynolds’ code, with its hidden obscenities and vertical scrolling sorcery, captured the era’s spirit—translating icy slopes into living-room triumphs.

Verdict: A foundational, if flawed, masterpiece. US Ski Team Skiing may not have aged gracefully, but its DNA courses through modern sports games. For historians, it’s a vital artifact; for retro gamers, it’s a charming time capsule. In the pantheon of skiing games, it’s not the fastest run, but it carved the trail.