- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Browser, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: increpare games

- Developer: increpare games

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Course movement, Globe control, NPC interaction

Description

Via Dolorosa is an abstract action game by increpare games where players control a globe that moves along a descending course, encountering simplistic polygonal human-like figures who confide their existential angst and sorrows about life’s hardships.

Via Dolorosa: A Review of a Digital Ephemeron

Introduction: An Obscure Artifact of Existential Reflection

In the vast digital archives of video game history, certain titles exist not as landmark releases but as haunting, nearly indescribable fragments. Via Dolorosa, a 2010 freeware release from the prolific but notoriously enigmatic indie developer Stephen Lavelle (under the increpare games label), is precisely such an artifact. It represents a deliberate, minimalist counterpoint to the increasingly complex and narratively dense games of its era. This review argues that Via Dolorosa is less a conventional game and more a brief, poignant interactive meditation—a digital Stations of the Cross for the modern existentialist. Its legacy is not one of commercial or critical acclaim, but of profound, understated artistic statement, existing at the very fringes of the medium’s definition.

Development History & Context: The increpare Aesthetic

Via Dolorosa emerges from the solitary, fiercely independent practice of Stephen Lavelle. The MobyGames credits confirm Lavelle as the sole developer, a consistent pattern for increpare games titles which, over decades, have produced dozens of short, experimental works exploring abstract mechanics, personal narrative, and unconventional interfaces. Released in July 2010 for Windows, Mac, and browser (via Unity Web Player), the game was made available as freeware, emblematic of Lavelle’s ethos of pure, uncompromised creative expression outside market pressures.

The technological context is the maturation of the Unity engine as a tool for rapid, cross-platform indie prototyping. This allowed Lavelle to create a geometrically simple 3D space (a “course” or path) and populate it with basic polygonal models without the burden of high-fidelity asset creation. The gaming landscape of 2010 was dominated by the rise of the digital distribution paradigm (Steam, Xbox Live Arcade) and a surge in narrative-driven indie games (Limbo, Fez). Via Dolorosa stands apart from these trends; it is neither a puzzle-platformer nor a story-rich adventure. It is an esoteric piece of interactive literature, released quietly onto an internet already saturated with content. Its obscurity is baked into its distribution model and its complete lack of traditional marketing or press engagement.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Unbosoming of Angst

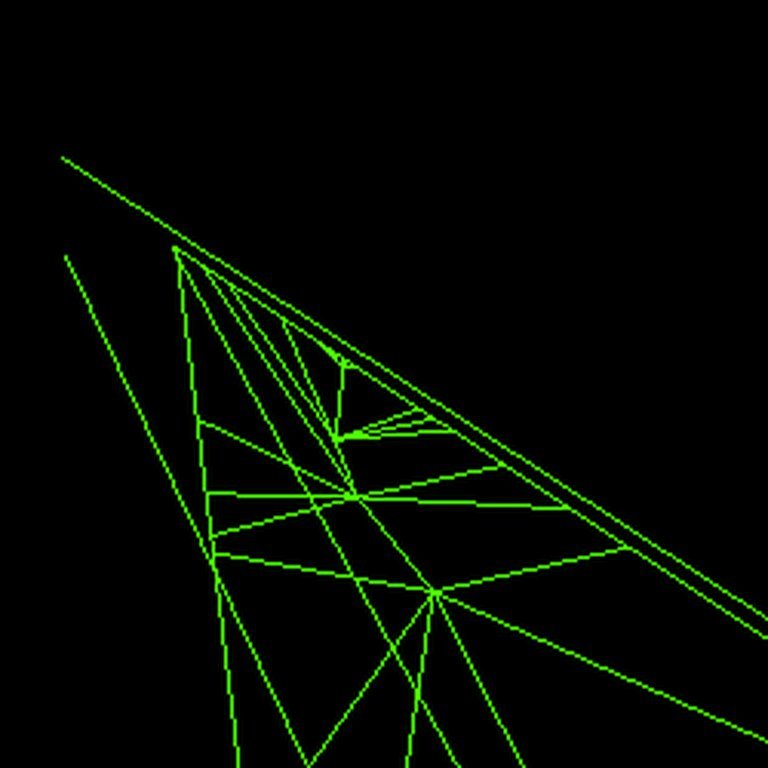

The game’s description provides the sole, stark foundation for its narrative: “We have control over a globe, that can move backwards and forwards on a course, descending it in any case. While moving down, the globe encounters human-like polygonal figures, who unbosom to it their angst for the sorrows of life.”

This is not a plot but a ritualistic framework. The player controls an abstract, spherical avatar—a pure geometric form—on a mandatory descent. The path is linear and inevitable, echoing the theological concept of the Via Dolorosa itself (the “Way of Suffering,” the path Jesus walked to his crucifixion). The “descending… in any case” suggests a gravitational, perhaps metaphysical, pull toward some lower, more fundamental state of being.

The “human-like polygonal figures” are the narrative engine. They are not characters with names, histories, or arcs. They are vessels of “angst,” a specifically Kierkegaardian or existentialist term denoting the dizziness of freedom, the burden of consciousness, and the sorrow inherent in existence. Their “unbosoming” is a confession, a stream-of-consciousness outpouring of lament. The themes are thus explicitly philosophical and universal: suffering, mortality, regret, and the weight of human consciousness. The game posits a world where sentient forms, crude as they are, are compelled to articulate their despair to an indifferent, spherical observer (the player). It is a silent, interactive parade of monologues from the dispossessed, each stopping the globe’s descent momentarily to share their grief before the inevitable journey continues. There is no resolution, no catharsis offered to the globe or the player—only the accumulation of voiced sorrow.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Mechanics of Descent

The core gameplay loop is described with breathtaking simplicity:

1. Control: The player guides a globe “backwards and forwards” along a predetermined “course.”

2. Progression: The course is a descent. Movement is likely binary (forward/back) with no stated ability to stray from the path. The “any case” in the description may imply the path’s inevitability, but the phrasing “descending it in any case” could also mean the player can choose to descend at their own pace or even retreat, though the overall trajectory is downward.

3. Interaction: Upon encountering a polygonal figure, the figure delivers its text-based “unbosoming.” The description does not specify if this is triggered by proximity, requires a button press, or is automatic. There is no mention of user choice in response—the players listens. The interaction is purely receptive.

4. Systems: There are no stated systems for combat, health, inventory, skill trees, or failure states. The “game” is the traversal and reception. There is no score, no objective beyond continuing the descent, no puzzle to solve. The “progression” is the sequence of monologues.

5. UI & Innovation: The user interface is presumed to be minimal, perhaps just the 3D view of the path and the globe, with text boxes overlaying the scene during encounters. The innovation is not mechanical but conceptual: it frames a linear sequence of reading in the spatial language of a 3D game. The “course” is a narrative timeline. The innovation is the use of a navigable 3D space to sequence and pace a series of literary fragments, creating a unique, embodied reading experience. The primary “flaw,” from a conventional perspective, is the total absence of agency or interactivity beyond navigation, making it more of a kinetic poem than a game.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic of Abstraction and Sorrow

The world of Via Dolorosa is defined by its radical austerity. The setting is a single, abstract “course.” There is no named location, no geography, no ecology. The atmosphere is conveyed through the stark geometry of the low-poly environment (reflective of early 2010s Unity aesthetics) and the pervasive thematic weight of the monologues. The “human-like polygonal figures” are deliberately crude, reducing humanity to its barest spatial form. This artistic choice reinforces the theme: these are not individuals but archetypes of suffering, their humanity rendered abstract by their geometric representation and their shared, generic “angst.”

Sound design is not mentioned in the source material. One can infer a sparse, ambient, or completely silent soundscape, punctuated only by the appearance of text. This lack of traditional audio cues (music, sound effects) would heighten the focus on the written word and the feeling of solitary traversal. The visual and auditory minimalism works in concert to strip away all distraction, forcing the player to confront the raw, textual delivery of existential despair. The environment is not a world to explore but a corridor to traverse, a procedural conduit for sorrow.

Reception & Legacy: The Silence of the Sphere

Critical and commercial reception for Via Dolorosa is virtually non-existent, as documented by MobyGames. It holds a “Moby Score” of n/a. Only 3 players have recorded “collecting” it on the site, and crucially, there are zero written reviews—neither professional nor player. Its audience is a handful of curious archivists and perhaps a small community within the niche of experimental game poetry.

Its legacy is entirely tied to the shadow of Stephen Lavelle’s broader, more recognized work (such as Hypnospace Outlaw, for which he is the lead designer). Within the milieu of “art games” or “not-games,” Via Dolorosa is a known but rarely discussed curiosity. It predates the widespread conversation around “walking simulators” and “games as poetry,” yet fits squarely within that lineage. Its influence is indirect and philosophical rather than mechanical. It serves as a citation point for discussions on ludonarrative dissonance (where the act of playing contradicts the narrative—here, the playful navigation of a globe contrasts sharply with the tragic content), on the use of space to pace text, and on the most minimal definition of an “interactive experience.” It is a ghost in the machine of indie game history, remembered by aficionados of increpare’s catalog as a particularly stark and forbidding entry, but having no discernible impact on subsequent mainstream or even indie design.

Conclusion: A Perfect, Forgotten Circle

Via Dolorosa is not a game to be evaluated on scales of fun, challenge, or narrative satisfaction. It is a successful, albeit niche, execution of a specific artistic vision: to create a solemn, interactive ritual of listening. Its mechanics serve its theme with ruthless efficiency. The descent is inexorable. The avatars are faceless vessels. The player’s role is passive witness.

Its “place in video game history” is as a touchstone of extreme minimalism and thematic purity. It demonstrates that the fundamental verb of a video game—to move an avatar through space—can be divorced from traditional goals and repurposed as a tool for structuring meditative, literary content. For every player who finds its lack of agency frustrating, another might find its unwavering focus on existential monologue powerfully resonant.

The final, definitive verdict is that Via Dolorosa is a perfectly realized, if profoundly obscure, piece of interactive art. It achieves exactly what it sets out to do with a minimum of elements, and then promptly vanishes into the digital ether, a tiny, dark sphere rolling silently along its predetermined path, its whispered stories of angst lost to all but the most determined archivists. It is a testament to the fact that within the expansive taxonomy of play, there remains a space for works that are not meant to be enjoyed, but to be endured—a digital via dolorosa for the solitary player.