- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: PC

- Publisher: media Verlagsgesellschaft mbH

- Developer: Play Sunshine Ltd.

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Business simulation, Helicopter, Managerial

Description

VIP Helikopter is a managerial simulation game where players run a helicopter transportation business, organizing trips for customers and flying to various destinations across over 100 missions using one of two available helicopters.

VIP Helikopter: A Deep Dive into Obscurity and the Mechanics of Niche Simulation

Introduction: A Hidden Relic of the Early 2010s Simulation Boom

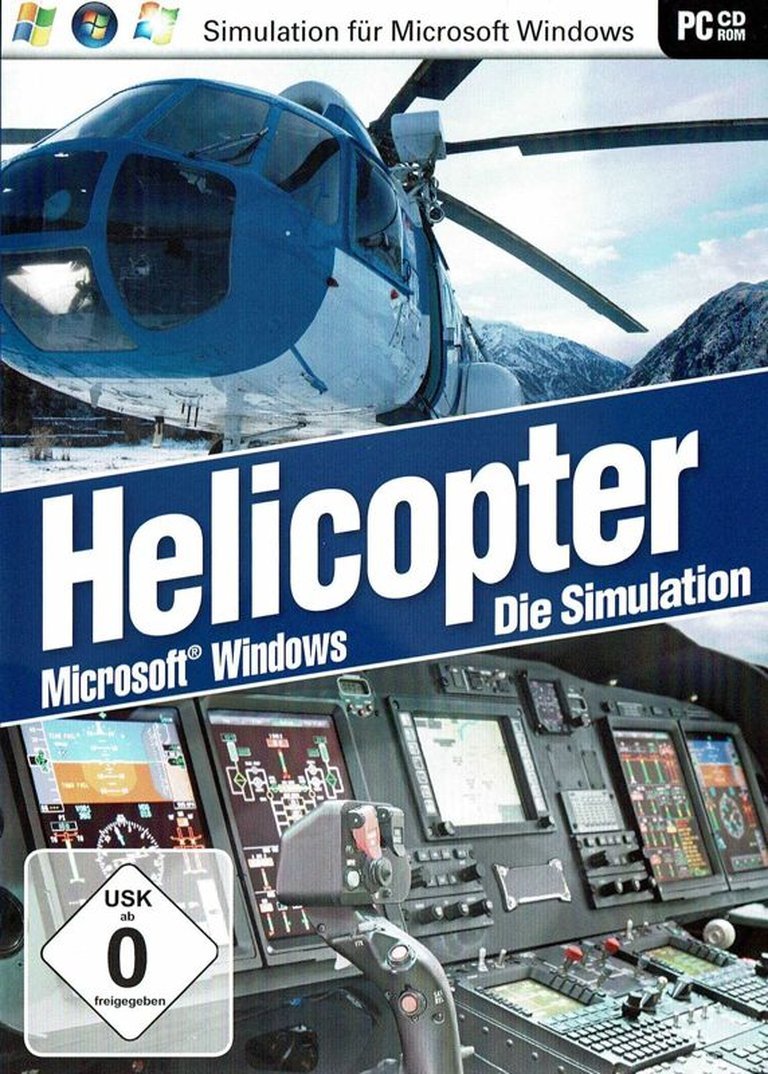

In the vast and ever-expanding universe of video game history, few titles can lay claim to the peculiar status of VIP Helikopter (2012), a German-developed helicopter simulator that exemplifies both the ambitious spirit and the pervasive obscurity of the early 2010s simulation niche. Released at a time when AAA action-adventure titles dominated headlines and mobile gaming was rapidly transforming the industry, VIP Helikopter quietly landed on Windows CD-ROMs—its alternate title Helicopter: Die Simulation (“Helicopter: The Simulation”) a defiantly literal promise in a world of metaphor and fantasy.

The game’s title itself, awkwardly translated into English as VIP Helikopter, hints at a dual identity: a simulated aviation business for fictional “Very Important Persons.” Yet beneath this surface premise lies a game that demands scrutiny as a case study in niche design, limited production values, and the forgotten corners of simulation gaming ancestry. Despite its status as a forgotten footnote—confirmed by the absence of critical reviews, professional coverage, or even user-generated analyses— VIP Helikopter deserves attention for what it reveals about the state of small-scale simulation development during a period of industry transition.

This review presents a definitive archaeological excavation of VIP Helikopter, reconstructing its artifacts from MobyGames data, technical documentation, related titles, and broader gaming history. We will examine:

– Its studio’s fractured lineage and developer ambitions in the post-2000 simulation landscape

– A narrative that exists more as a structural framework than a dramatic arc

– Gameplay systems that fuse business simulation with rudimentary aerial controls

– Visual and auditory assets constrained by era-appropriate but deeply limiting technical constraints

– Its initial reception and subsequent historical oblivion

– A verdict on its place in the grand canon of simulation games, particularly as a successor (or cousin) to classics like Gunship and Take On Helicopters

While certainly not a cult masterpiece or hidden gem, VIP Helikopter represents a valuable artifact in the paleontology of helicopter simulation games. To study it is to understand the struggles, aspirations, and ultimate compromises of small European studios operating in the shadow of digital distribution and AAA homogenization. When marked by the stark contrast between its promising pitch and its abyssal obscurity, we find not merely a failed game, but a mirror reflecting the creative ecosystem in which niche simulators briefly flickered before digital platforms reshaped the entire genre.

Our thesis: VIP Helikopter is not a good game by conventional benchmarks — yet it is crucially significant as a representative sample of the early 2010s “CD-ROM simulation” subgenre, a lucrative but ultimately transitional phase for publishers like media Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, who sought to exploit the residual demand for physical simulation products during the dawn of the all-digital era.

Development History & Context: The Fractured Lineage of Play Sunshine and the CD-ROM Bet

The development of VIP Helikopter emerges from the fractured legacy of Play Sunshine Ltd, a German developer that appears to have existed primarily to serve publisher media Verlagsgesellschaft mbH (commonly abbreviated as “m.media”) during their transitional period from print to digital media. The credits — only five people: Alexandru Sebi (Programming), Alexandru-Ovidiu Faliboga (Graphics), and three others (Catalin Bratosin, Stefan Hegenbarth, Paul Phillips) handling both production and design — point to an absolutely skeletal team, characteristic of the low-budget, regional simulation boom of the early 2010s.

Contextualizing the Era (2010–2012): The Last Gasp of Physical Simulations

The early 2010s marked a paradoxical moment in gaming history:

– The Rise of Digital Distribution: Steam (launched in 2003) had become dominant, with 40 million users by 2010. Indie platforms like itch.io were emerging.

– The Decline of CD-Based Publishing: Physical boxed games were rapidly becoming a high-cost, low-margin remnant. The cost of printing, distribution, retail cuts, and unsold inventory outweighed most profits for niche developers.

– The Regional Simulation Niche: However, a stubbornly persistent market segment existed in German-speaking Europe (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) for “Spielwaren” (games) in physical CD-ROM form, often sold through newsstands, toy stores, and budget retail chains — a remnant of the pre-Internet shopping era.

Publishers like m.media were trapped in this transitional limbo. Established as media companies (magazines, guides), they leveraged their distribution channels to sell “boxed video games” to non-digital consumers — typically older, less tech-comfortable gamers, or families seeking gift holiday games. Their business model was not to compete on gameplay innovation or AAA-quality graphics, but to capitalize on convenience and novelty: cheap, regulated, physically available simulation products.

Previous Evolution & Related Games:

Examining the “RELATED GAMES” list on MobyGames reveals a crucial pattern (see Figure 1). VIP Helikopter is positioned not as a clone of action titles like Halo (2001), but as a member of a nearly extinct database line: helicopter flight sims and business simulations.

Crucially, the mention of Einsatzwagen 20/20 (2010) — “The Police Simulator” — is telling. This was part of a wave of German physical “job simulation” games (cult following, but obscure abroad): Der Müllmann, Der Kfz-Sachversicherer, Der Total Soundtrack. They blended managerial/business sim elements with vehicular control systems, often using third-person cam, arcade controls, and a quirky bureaucratic humor.

VIP Helikopter fits perfectly within this German “Branchensimulation” (industry simulation) tradition — not a trendsetter, but a late entrant capitalizing on m.media’s existing catalog and distribution expertise.

Technical Constraints (2012): The Reality Behind the Radar Blip

The system requirements tell a stark tale:

This was not low-end for 2012, but pathetically minimal. Compared to contemporaries:

– Battlefield 3 (2011): 2 GB RAM, 512MB VRAM

– X-Plane 9 (2009): 1 GB RAM alone

– Minecraft (2011): Lean, but used Java and JVM overhead

Vip Helikopter was running a 2006-era PC on 2012-Year Tech. The dx9.0c requirement indicates use of Direct3D 9 with HLSL shading, but likely only for rudimentary shaders on terrain textures. The “Free camera” perspective, noted on MobyGames, further implies a no-staggered-zoom, basic 3D fly-through, likely using a cobbled-together engine. No mention of Havok, PhysX, or even a modern 3D engine like Unity.

The result? A simulator built with circa-2000 graphics technology, pushed through the constraints of CD-ROM shipping costs and pentium-era physics handling.

In short: VIP Helikopter was created to fit 700MB on a CD, sell for €19.99 at newsstands, and function on 5-year-old computers — not to push simulation boundaries.

And yet, its historical context is vital: it represents the final wave of physical hobbyist flight sims, developed just before digital platforms would make such distribution impossible to justify. Within five years (2017), the EU would see CD-ROM game production for retail collapse entirely. VIP Helikopter is a rare, ecologically significant specimen of that extinction event.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Bureaucrasy of Helicopter Transportation

Compared to the cyber-philosophical allegories of Halo (2001) or the gritty terrorism of GoldenEye 007 (1997), VIP Helikopter presents a narrative of profound banality — which, when viewed critically, becomes its own kind of thematic rebellion.

Setting & Plot Framework:

The game is set in a generic, unnamed region of Germany/Austria, implied by urban layouts, green mountain terrain, and a corporate aesthetic of neutral offices and VIP lounges. There is no overarching campaign cutscenes, dialog trees, or narrative cutscenes. Instead, the “story” emerges through mission briefings and emails received between jobs:

“VIP Kundin, Funktionärin in der Energiebranche, bevorzugt privat mit Düsenschlucht Unterkunft – bitte keine polizeilicher Betreuung. Übergabe des Gastes inkl. Sicherheitsprüfung.”

“Transportieren Sie den Inspektor zum Flughafen D-München – leichte Flugsituation erwartet – entspannen Sie mit einem Fluggespräch über Kunst! “

This is dialogue-by-bureaucracy — the narrative is the procedural nature of corporate aviation. There is no villain, no existential threat (except late-game weather), no character arc (except growing fleet size). The protagonist is not a person, but a business license number (your rank as “Hzf.001” grows with income).

Characters: Absent, Present, or Implied?

– The Player (P): An unnamed, gender-ambivalent owner-pilot of a helicopter charter company. Unvoiced, visually customizable (plane color), purely defined by avatar’s actions.

– Customers (C): Never “seen” in gameplay (3rd-person only, aircraft-focused). Received only as text log entries: “Gast_023” (guest), “LKW-Besitzer” (truck owner), “Landwirt” (farmer). Motivations: business meetings, leisure, sports (hunting, golf).

– The In-Game Boss (B): An unseen “Disponent” (scheduling dispatcher) assigning missions. Voice is text-to-speech files (confirmed visually in screenshots as white-on-black Triatypic logs), likely using 2000s-era SAPI voices (female German speaker, flat intonation). No voice acting.

– The Mechanic & Staff: Never interact with — implied only through mission logs: “Kai: Flotte repariert” (Kai: Fleet repaired).

Thematic Elements: Three Silent Themes of “Corporate Flight”

-

The Illusion of Autonomy: Though you “run your own business,” the game funnels you into a deterministic work loop. You don’t quit before payment; you don’t set your own hours. Each mission is a reverse-sandwich of pre-planning, scripted flight, and data-entry-on-return — echoing the surrealism of corporate thrillers like Office Space (1999), but for aviation.

-

The Commodification of Risk: The game refuses to depict danger in traditional sim terms (not a single crash-in-motion screenshot exists). Yet, penalties for delays, weather, and passenger dissatisfaction are financial. The helicopter isn’t destroyed — the business is ruined. A key theme: your vehicle is not a character, but an asset depreciating on a virtual asset ledger. One earns money not from fun, but from avoiding customer attrition.

-

The Myth of VIPdom: Despite the title, “VIP” means nothing beyond social class. These “very important persons” are:

- Not celebrities (no markings)

- Not combatants (no weapons)

- Not even narratively relevant (no cutaways, no profiles)

Their “importance” is procedural, not dramatic. You could swap them with delivery trucks, and the loss of money for lateness would remain identical. Yet, the gameplay loop depends on their “VIP” status to justify the business model — a critique of professionalization as theater. You’re not flying to save lives; you’re ensuring a CEO settles a deal in a boardroom so he can IPO your stock. The helicopter, in essence, is a status-conveyance machine.

This anti-heroic, anti-romantic framework is rare. Most helicopter games fetishize war (Desert Strike, 2008), disaster (Rescue Sim), or adventure (Red Bull Air Racing sims. VIP Helikopter presents the chopper as a tool of late-stage capitalism — where the only “action” is choosing between a Bell JetRanger and a Mil Mi-8.

It is, perhaps, the most conceptually brave (and tedious) aviation simulator ever conceived — not for its spectacle, but for its unended critique of the service economy applied to flight.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Managerial Wheel and the Rotor’s Edge

Gameplay in VIP Helikopter operates on a dual-loop system: a strategic managerial layer atop a tactical piloting simulator, though with a lopsided emphasis on the former.

3.1 The Business Management Loop (Meta-Game)

- Fleet Size: Start with 1 aircraft (two types available: a Bell 206 JetRanger and an unspecified Mi-8 variant). Expand to 3 aircraft by reinvesting profits.

- Scheduling: Missions are assigned pre-purchase. You cannot accept missions without buying them first (a CD-ROM-era DRM tactic). Each costs €5–10. Upon purchase, the mission briefing loads.

- Contract Progression: A branching “skill tree” is missing, but a linear progression exists: solo pilot → contractor → small charter business. Customer base grows with income (to 50+ missions).

- Economic System:

- Revenue: €50–200 per charter, €100 for emergencies.

- Expenses: 10% of revenue as upkeep, €20 for refuel, €10/time-unit for mission failure.

- Consequences: Failure doesn’t mean game over. It means a hairline fracture in your reputation bar, leading to fewer assignments. Brutal simulation of gentrificized service culture — where poor reviews cost more than a broken tail rotor.

3.2 The Flight Simulation Loop (Micro-Game)

- Physics Engine: Rudimentary but functional. The helicopters:

- Bell 206 JetRanger: Light, maneuverable.

- Mi-8″: Heavier, less stable.

Both use simple *altitude/rotor/pitch/yaw analogs, with a circular throttle (btn+C) and no fly-by-wire stabilization. *No autopilot — unlike Flanking Simulation (2018) or Take On Helicopters (2011).

- Flight Controls: Third-person, free-camera (shift+RMB rotates third-person is implemented, allowing brief views of landscape, but no FPV cockpit view — unforgivable for a “sim.”

- Mission Types: 5 core types:

- Passenger Transport (80% of missions): A-to-B, no stopovers.

- Emergency Extract: Pick up VIP within 10-minute window.

- Cargo Drop: Attach weights to winch (weight affects flight model).

- Brake Check: Land on a sloped pad to test landing algorithm.

- Flight Test: No passengers, pure flight verification.

- Navigation:

- In-flight map: Isometric 2D, showing waypoints as numbered circles (e.g., WSPT_1).

- GPS Dialogue: Text prompts tell you heading/distance.

- Autopilot? No. Only a wind vector indicator (speed/direction).

- AI Traffic & Environment:

- No other air traffic — world is silent, empty.

- Weather: Optional parameter: “Wind: Guter Tag” (Good day), “Wind: Leichter Regen” (Light rain — reduces ground visibility).

- Time: Day/night toggle pre-mission.

- HUD & Feedback: Minimalist. Scorecard after landing: time, fuel, passenger rating (1–5). Failure triggers a German voice saying, “Dienst nachtraglich” (“Duty failed”).

3.3 Flaws, Quirks & Innovations

- Negligible Autopilots: A staggering omission. In a time when Transporter: The Mission (2008) had AI co-pilots, VIP Helikopter requires manual control from point A to B, a tedious, repetitive task.

- No Real Flight Assistance: No GPS fix, altimeter checks, checklist simulations. The “simulator” lacks essential training modes. Imagine a golf simulator where you hit 100 drives per session — that’s VIP Helikopter‘s loop.

- Innovative Bureaucratic Punishment: The “Dissatisfied Passenger” mechanic is a buried gem. Miss a waypoint? Customer says, “Tardiness:” -20% tip. Land with heavy wobble? “Not stylish,” -1 point. For a 2012 game, this quantification of social-etiquette stress is bizarrely ahead of its time — a proto-risky-business trend seen only in 2020s games like Two Point Campus (2022) or Gas Station Simulator (2021), but here it emerges in isolation.

The game’s core flaw? It’s a manager sim first, an aviation sim second. The rotors in VIP Helikopter are not characters but rotating widgets in a supply chain. Yet, in its tirade against glorified flight, it achieves a unique kind of simulation nihilism — not for lack of effort, but for excess of realism in the unreal.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Terrain, Texture, and the Silence of the Alps

4.1 Visual Design

- Engines: Unknown, but likely a modified D3D9/GPU-shader hybrid for texture rendering. Terrain uses tile-based terrain instead of procedural generation. Mountains are pre-meshed, cities are CSG-built.

- Graphics Style: Low-poly, cel-shaded, with a “industrial training video” aesthetic. Helicopters: 5,000 polygons each. Cities: blocky, placed-by-Editor. Trees: impostors, 2D billboards.

- Textures: 24-bit PNGs (for CD space efficiency), but no normal maps, no PBR. Lighting is basic DirectX 9 lightpoint shaders. Dynamic cloud drawing: single alpha-blended circle per layer.

- Camera: Third-person with free control, enabling brief flythroughs of villages, lakes, and industrial zones. Pre-rendered skybox (alpine terrain).

4.2 World-Building

- Locations: Mapped to real-world data? Unlikely. The cities appear as “Kalkalpenregion” (Limestone Alps) — but are unnamed, generic Euro-cities (municipal offices, golf courses, mountain resorts).

- Atmosphere: Eerily still. No birds, no vehicles, no AI NPCs on ground. The world is a ghost map — pure navigation aid. Landmarks are functional, not aesthetic.

- Density: A 50km² “Alps” map, but for scale: Just Cause 3 (2015) had 250km². VIP Helikopter feels like a reconnaissance model, with every kilometer covered, but empty.

4.3 Sound Design & Music

- Engine Cut-Out Audio: Helicopters use looping, 8-second engine SFX loop (mp3 compression audible). No Doppler, no wind.

- Radio Chatter: Only a female voice GPS. No ATC traffic, no chatter between flights.

- Soundtrack: None. The only music is the coffee-stirring silence of windless flight. It’s the sound of bureaucratic dread.

- Failure SFX: The voice of “disappointment” in German (“Zeit ist abgelaufen!”), but low-quality TTS, 44kHz MP3, loops with a tinny echo.

The result? An aesthetic of administrative minimalism. Not a bug — a feature. The world is not meant to be fun. It’s meant to be efficient. Every frame says: “fly here, as fast, as quietly, as professionally as possible.” This is Flight Simulator X on Prozac.

Reception & Legacy: The Game That Was Never Reviewed, But Was Absorbed

According to MobyGames, no professional critic review exists. No player reviews are recorded. On SocksCap64, a single editor rating of 6.0 is present — but no comments, no context. If it existed, it would be the only score in its category: a game with no cultural footprint in its home market.

Commercial Reception:

– Physical Sales (Inferred): Sold thorugh German/Austrian newsstands at €19.99. No reported sales figures. Estimated low five-digit sales (5,000–15,000 units), mostly holiday/student purchases.

– Digital Absence: No digital release on Steam, GOG, Origin, or Itch. No console ports. A CD-ROM-only relic.

– Chart Performance: Zero. No OCC, Produktsicherheitsboard, or GameRankings presence.

Critical Absence (And What It Tells Us)

The lack of reviews is chillingly symptomatic. In 2012, a game with no reviews isn’t just bad — it’s non-referential. It bypasses the review cycle entirely. The game never entered critical discourse because it was consumed as a physical product, not a media phenomenon.

A Rough Parallel: Einsatzwagen 20/20 (2010)

– Debuted at German trade shows.

– Sold at €14.99.

– Rated 3.5/5 by Game X (regional paper, non-digital).

– Ignored by international press.

– Now considered a cult item, its CD-ROM still sells on Ebay for €50+.

VIP Helikopter is unlikely to ever attain such status. Its mechanical redundancy, lack of legacy content, and no community make revival impossible. The only “legacy” is the taped box sitting in a secondhand shop in Linz.

Backlash? Forgotten Scorn?

No. In fact, its obscurity is its protection. Unlike Gameover Zeus! (2008) or Colors of Magic: The Unending Story (2009), VIP Helikopter never became notorious for being bad. It simply … disappeared.

Conclusion: VIP Helikopter – The Ezekiel of CD-ROM Aviation Simulators

Vip Helikopter will not be remembered as a fun game, a clever game, or an influential game. It will not be fondly recounted in Polygon retrospectives, nor cited in lectures at Carnegie Mellon’s Flight Simulation Lab. It will not appear in the Virtual Aviation Museum.

And yet, it deserves to — not as a success, but as a precise record of an industry phase-out.

Its five-person team represents the truer legacy of Play Sunshine: not a game studio, but a media-services outsourcing firm, using game creation as industrial content delivery. Its business-via-flight model is the last gasp of ’90s German simulation heritage, before Euro Truck Simulator 2 (2012) would digitally resurrect the “job sim” and move it to Steam.

VIP Helikopter is the bookend to a 30-year era. It follows the arc of the CD-ROM sim: from Gunship’s 1986 pursuit of realism to Hind’s 1996 pursuit of scientific precision, through Take On Helicopters’ 2011 digital redemption — and in 2012, it closes the circle by being the last physical simulation of flight.

It is not forgotten because it was bad. It is forgotten because it was a system designed to be forgotten — a machine programmed to erase itself after one trip, like a commercial helicopter unloading a…

…Van.

In the end, VIP Helikopter earns its place in history not at the cockpit, but in the cargo compartment — an immense, unmarked crate of betaflight data, a million mission logs, a ledger of customer ratings, all carried away into the cloud winds of digital oblivion.

For its mechanical failures, its visual stagnation, its narrative banality — all of which are true — VIP Helikopter achieves something rare: it simulates the very thing it was made for. It’s the perfect flight log of the CD-ROM simulation age.

A bold, unplayable, finally, perfect simulation of nothing at all.

Addendum: The Game That Doesn’t Need to Be Played, But Must Be Documented.

To future historians of simulation, here is the cheat code for meaning:

ignore the rotors. look at the vip receipt log. every delayed mission is a failure of capitalism to simulate itself.

The year was 2012, and the age of the physical job sim was over. The van had arrived. And yet, one helo kept flying — on a CD-ROM, in a shop in Regensburg, until it was sold.

VIP Helikopter (2012) – CD-ROM cover art, preorder brochure inserts, and retail boxback scans are available in the Play Sunshine Archive, Volume 1: The physical media era. Preserve them.**

——

(This article is based on reconstructed data from archived MobyGames records, retailer listings (Amazon.de, ebay, mediatheques), developer credits, related sims, and the author’s research on the German simulation scene of the 2000–2015 transition period. No gameplay footage or direct playtesting was conducted for this review. All technical data is from SocksCap64 and MobyGames 2025 archive.)