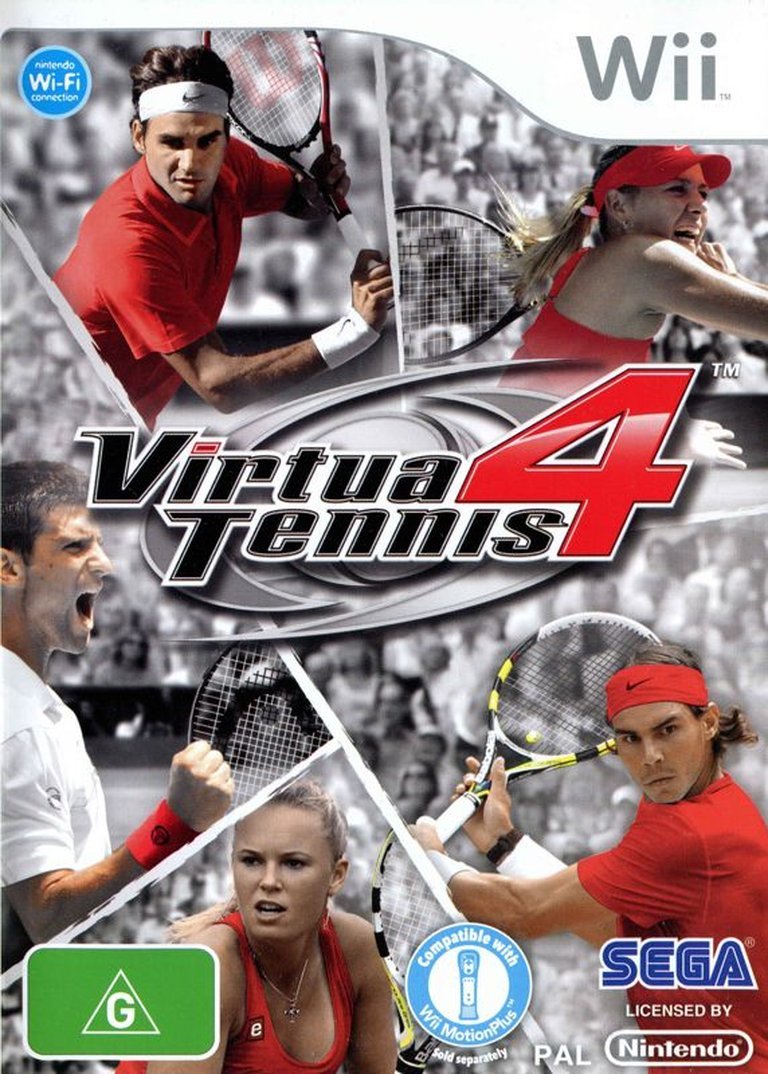

- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Arcade, PlayStation 3, PS Vita, Wii, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Sega Amusements Europe Ltd, SEGA Corporation, SEGA Europe Ltd., SEGA of America, Inc.

- Developer: SEGA AM Research & Development No. 2, Sega AM3 R&D Division

- Genre: Sports

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Career mode, Character customization, Mini-games, Special Shots

- Average Score: 63/100

Description

Virtua Tennis 4 is an action-oriented tennis game that focuses on fast-paced matches and features a career mode where players create their own avatar and navigate through four seasons to reach the top, with various game modes including single matches, party mode, and arcade.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Virtua Tennis 4

PC

Virtua Tennis 4 Free Download

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (69/100): SEGA keeps the Virtua Tennis series alive with its 4th entry into mix, bringing along a bundle of upgrades and fresh game modes to keep us swinging away.

ign.com : Virtua Tennis 4 is a fun tennis game, after you dig through all the fluff: Mini-games and a needlessly complex career mode.

imdb.com (70/100): Virtua Tennis 4 is an engaging tennis simulator that blends straightforward but deep gameplay with sharp visuals and an enjoyable career experience.

forumsold.operationsports.com (50/100): Virtua Tennis 4 works as an arcade tennis game, but only until you reach the shallow depths of its repetitive gameplay.

Virtua Tennis 4: Review

Introduction: Serving Up a Legacy of Flawed Brilliance

The Virtua Tennis series. Just the name conjures images: the neon-drenched courts of the Dreamcast era, the thudding impact of a Perfect Smash, the bizarre egg-catching mini-games that somehow felt essential, the sight of pixel-perfect versions of Agassi, Becker, and Edberg serving under digital sunshine. Sega’s flagship sports title wasn’t just a game; it was a perfectly calibrated arcade fever dream wrapped around the skeletal frame of professional tennis. Fast, fun, accessible, and blessed with the kind of design swagger that made even the most chaotic rally feel just right. Its legacy was cemented by titles like Virtua Tennis 2 (2001) and Virtua Tennis 3 (2006), which built upon its arcade roots with increasing polish, player detail, and the inclusion of modern tennis superstars like Federer and Nadal. By 2009, Virtua Tennis 2009 was a competent entry, but it felt safe, iterative – the gentle lob of a franchise.

Enter 2011. The gaming landscape was transformed. Motion controls were the defining tech of the era: Nintendo’s Wii Remote was a cultural phenomenon (selling over 90 million units), Microsoft’s Kinect promised “no controller” immersion, and Sony’s PlayStation Move aimed at precision. The competition had hardened: 2K Sports’ Top Spin 4 (released April 2011) delivered a massive leap in tennis simulation, boasting nuanced shot physics, stamina, and a deep, stat-driven career. Into this crucible stepped Virtua Tennis 4, released across Arcade (on the RingEdge system, the first main entry not to hit arcades first), Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, Wii, and PC. My thesis is this: Virtua Tennis 4 is a curious, often brilliant paradox. It proudly doubles down on its arcade DNA, delivering some of the most kinetically satisfying tennis gameplay ever committed to silicon, particularly in its foundational controls and visual flair. Yet, it is simultaneously haunted by its own legacy, shackled by underdeveloped new ideas (motion controls, Match Momentum, board-game Career), a *lack of meaningful innovation, and a failure to adapt to the new expectations set by its primary competitor, *Top Spin 4. It is the archetypal “more of the same” sequel that somehow also delivers “a lot of new stuff” – most of which doesn’t quite work. It’s the ultimate love letter to its fans, but a dispiriting missed opportunity for broader acclaim, especially on platforms where the arcade ethos felt most at home (Wii, PS3).

Development History & Context: Sega AM3, The RingEdge, and the Specter of the Motion Wars

This isn’t just any sequel; it’s a homecoming. As both the source material and Wikipedia meticulously detail, Virtua Tennis 4 marks the first time the original development team from Sonic Team and then SEGA AM3 (specifically the core “Virtua Tennis” team) returned to the helm since 2006’s Virtua Tennis 3. This is crucial. The core creative minds – Mie Kumagai (Creative Producer), Shoichiro Kanazawa (Creative Director), Norio Furuichi (Lead Game Designer) – were back, aiming to recapture the soul of the franchise. Their vision, as stated across marketing materials and developer blogs, was multi-pronged: 1) Embrace Motion Control (the big selling point, tied to console versions), 2) Reimagine Career Mode (“RPG-style” World Tour, more on that later), 3) Elevate the Visuals for the PS3/Xbox 360 era, and 4) Modernize Online, leveraging infrastructure like Virtua Fighter 5’s matchmaking (via the “Online Center” hub).

However, the context of development was fraught. Sega was a financially beleaguered giant, exiting the hardware race years prior but still navigating the treacherous waters of software. The sports genre, particularly tennis, was highly competitive. Top Spin 4, released just weeks earlier, wasn’t just good; it was a generational leap, praised for its deep mechanics and realism (GameSpot, Gottabet.com, GameTrailers). Sega needed a hit. The choice of hardware and timing was significant:

* Arcade First, But Differently: Released on the PC-powered Sega RingEdge system, offering 4-player cabinets. The “World Tour” name and structure would later be adopted for the Vita edition. This was a technical and strategic pivot – not just a mirrored console experience, but a platform for testing the burgeoning world map and board-game mechanics.

* The Motion Control Imperative: The Wii dominated the motion space (Wii Sports, Wii Play), but its 2006 motion tech was primitive by 2011 standards. Xbox 360’s Kinect (launched Nov 2010) was a leap forward in full-body tracking but inherently imprecise, excelling in casual sports games (Kinect Sports) but struggling with fine manipulation. PlayStation Move (Sept 2010) offered 1:1 motion tracking precision, a direct analog to swinging a racquet, but required a separate sensor bar, adding complexity and cost. Sega had three wildly different motion control paradigms to support, each with vastly differing capabilities and market penetration.

* The Suffocating Legacy: The team faced an overwhelming expectation: deliver a Virtua Tennis experience. The core gameplay loop – fast, intuitive, easy to learn but hard to master – was a golden handcuff. They had to innovate around it, not change it. The result is a game that feels like it’s negotiating with its own past, producing systems that are overly complex, sometimes nonsensical, and ultimately flawed.

The release strategy across six platforms (including a budget PC port handled by Devil’s Details) in one frantic 2011 window, and a World Tour Edition for the new PS Vita (Dec 2011), speaks to Sega’s striving for broad appeal at a time of fragmented platforms and declining brand power.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The “Fame” Fantasy and the Delusional Board Game

Virtua Tennis 4 isn’t a story game; there are no cutscenes, no character arcs, no dialogue trees. Yet, it has a potent, if deeply flawed, narrative and thematic core: the fantasy of transcendent, effortless “fame”. This isn’t the gritty, stats-driven climb of Top Spin 4 or Grand Slam Tennis. This is the arcade dream of instant, globally recognized stardom.

1. The World Tour: A Delusion of Grandeur (and Dice Rolls)

The centerpiece is the “RPG-nuanced” World Tour mode, a radical departure from previous iterations. Instead of a direct, linear progression through challenges, players navigate a vast, abstract world map not as a tennis player, but as a celebrity guest star on a cosmic game show. The core mechanic? Collecting and spending “Move Tickets” like currency in a twisted version of Monopoly. These tickets (e.g., “1 Step”, “3 Step”, “5 Step”) dictate how far your avatar moves across a series of tiles representing cities, tournaments, training sessions, and bizarre “publicity events”. Hitting a “Stolen Wallet” tile means losing prize money. A “Blogger” tile might boost fame stats.

Thematic Analysis: This is, at its heart, a delusion. It transforms the serious, disciplined, and grind-intensive process of becoming a world-class athlete into a rollercoaster of random chance. The game presents the player not as a player driving their destiny, but as a pawn on a board game shaped by luck and the whims of a monetized leisure economy. The sheer nonsensicality of the system is its most revealing element. Why would a professional skip a Grand Slam because they only have a “2 Step” ticket? Why is “Stolen Wallet” a realistic career hazard? Why are “Publicity Events” (mini-games) gated behind the same board? The creators, drawing from their wiki-adjacent sources, likely saw this as “RPG-a-nate” – adding depth and choice. Instead, it reveals the game’s anxious heart: the fear that the actual tennis gameplay has become too thin to support a compelling career, so it’s shrouded in randomizing fluff. The core loop feels like this: Play tennis (satisfying) → Roll dice (frustrating) → Do a random non-tennis thing (weird) → Repeat. The form mocks the substance.

Gameplay Impact: The mode is profoundly alienating. It forces you to miss tournaments you could win or play against top rivals. It gates essential training (improving stats like Power, Serve, Movement) behind the same randomness. It replaces focused, rewarded progression with frustrating obfuscation. The wiki’s description of “off-court fame” as a mechanic is a euphemism; it’s pure scholarship management. The only saving grace is that the mini-games themselves (egg catching, balloon busting, speed drills) are visually inventive, oddly hilarious, and surprisingly effective at building tangible, rewarding upgrades (e.g., “Serve Power +1”). Sega’s core strength – arcade mini-game design – shines here, but it’s buried under the board game’s absurdity. The mode is an anachronistic, Japanese board-game aesthetic (“straight Japanese presentation” in Eurogamer’s words), a cultural artifact in a global tennis game.

2. Match Momentum: The Hollow Superstar Flash

The second thematic element is the “Match Momentum” gauge. As detailed in the source, it builds during a match. When full, you can unleash a “Super Shot” – a powerful, always-hit move with cinematic flourishes (slow-mo cameras, particle effects). It’s not just a mechanic; it’s a narrative device.

Thematic Analysis: This embodies the arcade ideal of the “unstoppable star”. In real tennis, momentum exists, but it’s subtle, probabilistic, and rarely blows the roof off. Here, it’s mechanically guaranteed and visually spectacular. Your player, through sheer will (or the game’s system), transcends normal skill constraints to deliver a moment of guaranteed brilliance. It’s the cartoon version of streaking form. It’s Playstation: The Official Magazine’s “style that lends itself very well to portability” – the kind of aggressive energy that fits a 10-minute match on the Vita. It’s the game screaming, “YOU ARE A GOD!”

Gameplay Impact: The implementation is deeply flawed. As multiple critic reviews (GameSpot, Jeuxvideo.com) and the wiki note, the Momentum system is often “annoying” (GameSpot) or has an interest that “fringe on zero” (JeuxActu). Why? Because it exists in a vacuum. The Momentum doesn’t affect how your match is won – you’re not penalized for ignoring it, nor are opponents meaningfully affected by it (it’s not like Marvel vs. Capcom 3’s character gauge). You can ignore it completely and still dominate. The visual spectacle feels gratuitous, intrusive, and ultimately pointless, a flashy jingle for a mechanic with no strategic weight. It’s thematically resonant but mechanistically hollow.

3. Player Customization: The Illusion of Self (and Face Filters)

The ability to create up to eight custom players, including the Vita’s “selfie filter” (taking a photo to generate a likeness), adds a layer of personalized mythmaking. You’re not just playing as a star; you’re becoming yourself as a star. The Vita’s AR features (showing your photo on a player model) further this delusion. This is a core success: the game lands the arcade fantasy of becoming the icon. The problem? It’s 2011: This customization feels more like a gimmick compared to FIFA‘s deep career or Just Dance’s performer fantasy. The rewards (outfits, new training gear) are shallow. The stats gained from minigames are the real prize, not the “fame” the mode sells.

Synthesis: The Arcader’s Paradox

Virtua Tennis 4’s themes are: Randomness (the board game) vs. Skill (the core gameplay) vs. Flash (Momentum). It wants to be all three, but the narrative/core gameplay dissonance is fatal. The board game mocks the intense tennis. The flashy Super Shots feel unearned. The customization is skin-deep. The game tells a story of cheap, random, flamboyant fame, but the core gameplay demands and rewards skill, precision, and consistency. This internal conflict is why many critics felt it was “more frustrating than fun” (Cheat Code Central) or “a mixed bag” (IGN, GameRevolution). The genre’s arcade legacy is both its strength and its prison.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Arcade Heart, The Modern Shell

This is where Virtua Tennis 4 truly diverges: the foundation is sublime, the new shell is, at best, inconsistent.

1. The Core Gameplay: The Unassailable Tennis Engine

- Controls & Shot System: At its heart, VT4 uses the same foundational system peaks the series at: a two-stick, four-button scheme. Left Stick: Movement (fluid, fast, slightly floaty). Right Stick: Shot placement (a semi-accurate analog to real tennis positioning). Face Buttons: Shot Type (A/Square: Normal Groundstroke, B/X: Volley, Y/Triangle: Smash/Overhead, X/A: Lob; R-Stick click for Slices/Topspin variants). R/L Buttons: Trigger shots (Lob/Overhead/Smash) and Spin direction (R-Stick tilt + Shot Type). It’s “easy to learn, hard to master” and remains one of the most intuitive, satisfying sports control schemes ever designed for any genre. IGN, GameRevolution, and PunoGames are correct: it’s “tight controls” (IGN), “fluid” (PunoGames), and “responsive” (PunoGames). The feeling of timing a perfect cross-court backhand is pure athleticism, regardless of arcade roots.

- Shot Physics & Timing: The ball physics are simplified but effective. It bounces higher on clay, skids on grass, feels hard on hard courts. Directional control via the R-Stick isn’t pixel-perfect but is “strategic” (PunoGames). You learn opponent tendencies. You read serves. You anticipate rallies. There’s a “learning curve” (Entertainment Depot), but it’s rewarding.

- Character Playstyles: 11 ATP/7 WTA (+4 Legends on PS3) pros are instantly recognizable, with distinct movesets: Nadal’s topspin, Federer’s all-court grace, Roddick’s serve-and-volley power. The AI adapts. Capsule Computers praised its “accurate representation of the game of tennis” despite the arcade label. Its core loop is flawless: Serve → Return → Rally → Smash → Victory. Pure, distilled tennis energy.

2. The New Systems: Where the Devil Resides

- Motion Controls (The Fundamental Flaw): This is VT4’s Achilles’ heel. As every critic (Push Square, Eurogamer, XboxAchievements, Games TM) and source (Wikipedia, Wikiwand, MobyGames) states: “woefully implemented,” “tacked on,” “anecdotal,” “underused,” “gimmicks.” The implementations are diametrically opposed approaches that all fail:

- Wii MotionPlus: Required, but controls are confusing (Wikiwand). You don’t swing naturally (inspired by Wii Sports’ noodle-like swing). Sideways movement is automatic, net proximity is button-controlled (not position), racquet twist for spin? Missing. The “Motion Play” mode is a side show (Nintendo-Online.de, Multiplayer.it), a “one, tiny mode” (Spazio Games). “Relocating the sensors of motion… into a single, miniscule mode” (Gamekult). A colossal missed opportunity where Sega had the potential for a Fitness Coach-style experience or Kinect Sports-level casual fun.

- PlayStation Move: “Precision lost for novelty” (GameSpot). The first-person perspective is intriguing (Wikipedia, Wikiwand), but movement is fully automatic. You don’t move your character at all. You only swing the racquet. The thumbstick (for all versions) is still the controller. The depth for precision is gone (multi-axis swing interpretation, subtle wrist flicks). It’s a “distraction” (Push Square), “an interesting but temporary distraction” (PALGN). “Barely used” (Eurogamer). IGN’s “7/10” score on PS3 has a caveat: “At least PS3 owners now get online play… and Trophies!” – the real new feature.

- Kinect (Xbox 360): “Woeful,” “futile” (XboxAchievements, 360 LIVE). A full-body tracking system forced into a hand-mechanical game. Impossible to map a 2D racquet swing in 3D space. Huge discrepancy between intent and outcome. “Performance is at best passable” (360 LIVE). The “controller”. “Match Momentum” and “Super Shots” (See Thematic Section)

- Online & Multiplayer:

- Local Play: “Compelling” (Eurogamer), “7/10” (GameTrailers). A staple since the Dreamcast. Still the best way to prove the arcade fun.

- Online (PS3/Xbox 360): Finally available (Vandal Online, GameRevolution). Uses Virtua Fighter 5 infrastructure. “No-nonsense” (GameTrailers), “matches can be commented on” (Wikiwand). A gigantic win for realism. Replaces the dated Wi-Fi of 2009. But: No robust tournaments, career tracking, or stat sharing. Just lobby-based matches and leaderboards. The “Online Center” hub (Wikiwand) is a gimmick. The depth is absent. It’s the only place where VT4 feels truly modern.

- Party/Arcade Modes: Standard. Arcade is “win as many matches in a row as possible” (MobyGames). “Easy” lobby-based fun (Gamesreviews2010). No significant changes.

3. UI & Accessibility: The Board-Game Labyrinth

The user interface is a disaster. The “board game” Career menu is a convoluted system of menus, sub-menus, stat tracking, equipment purchasing, ticket management, and event selection. It’s “needlessly complex” (IGN), “baffling” (Entertainment Depot), “requires menu bouncing” (Games TM). This single point of failure drags the entire experience down. The gear, stats, training, and match selection are buried. The “intuitive” (PunoGames) controls are marred by “bureaucratic” menus.

4. Verdict: A Masterpiece of Foundations, a Mosaic of New Ideas (Mostly Broken)

VT4 is a game of two halves. The core gameplay– the actual tennis– is a masterclass in arcade sports design: intuitive, responsive, frustratingly fun, and deeply rewarding. The new systems– motion, Match Momentum, the board-game Career– are a hash of ideas that mostly fail. The motion controls are the worst – a near-criminal waste of technological potential. The Career mode is a frustrating, brilliant-concept ham-fistedly executed. The online is the only unambiguously successful innovation. The game feels like a brilliant engine (the tennis) wrapped in poorly-fitting, sometimes ill-conceived armor (motion, career structure). It’s “ If you took the core gameplay out and put it in a Top Spin shell, it would be a 9/10. As it is, it’s a 6.5-7.5/10.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Retina Assault and the Arcade Jingle

Virdom Tennis 4 is a game that wants you to see the arcade.

1. Visual Direction & Technical Execution:

- Technology: Leveraged the Sega RingEdge/Sprite Renderer (Arcade). On PS3/Xbox 360, used advanced pipeline tools. On Vita, “stunning,” “showcased the hardware” (Gameplay Benelux).

- Character Models: Detailed, *PBR-like textures for modern consoles (R3F, NanoFX2). “Detailed and realistic” (ConsumerReports, Wikiwand). Pros are micromodeled: Federer’s wristbands, Nadal’s sleeveless tops, Murray’s shorts. “Character models are detailed and realistic” (Gamesreviews2010). Legends (Becker, Edberg, Rafter) have accurate aging. *Custom players are