- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Dartmoor Softworks GmbH & Co. KG, Russobit-M

- Developer: Dartmoor Softworks GmbH & Co. KG

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Isometric

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Board game

- Setting: Europe, Medieval

Description

Web of Power is a digital adaptation of a medieval strategy board game where players take on the role of a religious order leader, expanding their influence across Europe by constructing cloisters and dispatching councils. The game includes the ‘The Vatican’ expansion set, adding further depth to its tactical gameplay centered on isometric visuals and multiplayer competition for 2-5 players.

Web of Power: A Historical Analysis of a Niche Medieval Strategy Adaptation

Introduction: A Quiet Giant of the Digital Board Game Boom

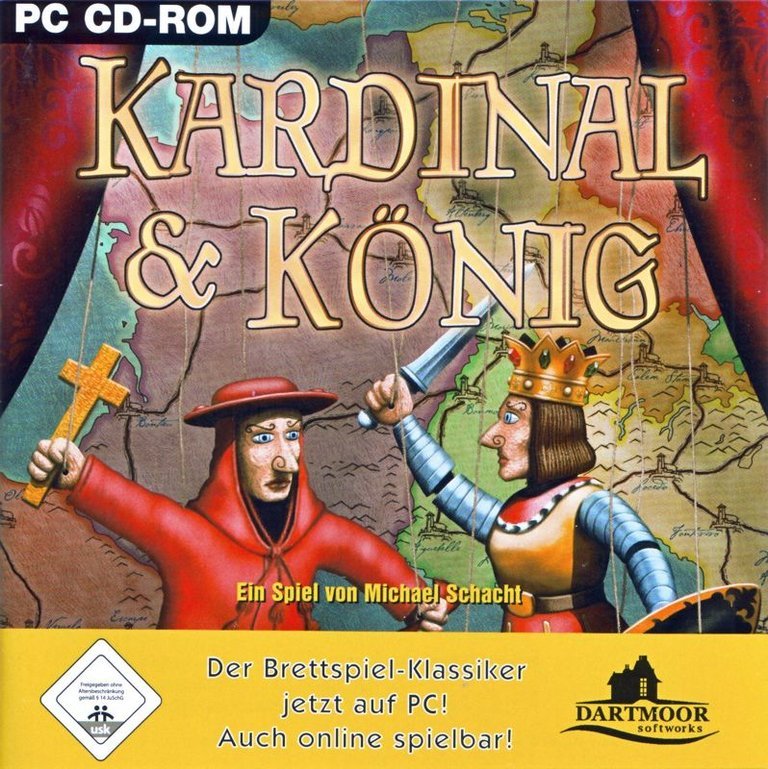

In the crowded annals of early 2000s PC gaming, where blockbuster franchises and innovative indies vie for attention, Web of Power (also known by its German title Kardinal & König) stands as a testament to a specific, fertile moment in game development: the earnest translation of European-style board games into the digital realm. Released on April 1, 2004, by the German studio Dartmoor Softworks GmbH & Co. KG, this strategy/tactics title adapted the acclaimed board game by Michael Schacht. Its premise—stepping into the robes of a medieval religious order leader, expanding influence by building cloisters and dispatching councils across Europe—speaks to a design philosophy valuing systemic depth over flashy presentation. This review argues that Web of Power is a significant, if overlooked, artifact. It embodies the careful, rules-first translation ethos of its era, offering a purist’s strategic experience that, while lacking the narrative bombast of its contemporaries, provides a clear window into the mechanical heart of its board game progenitor and the modest ambitions of a specialized developer at a technological crossroads. Its legacy is not one of mainstream impact, but of faithful preservation within a niche canon.

Development History & Context: Dartmoor Softworks and the German Board Game Bridge

The story of Web of Power is intrinsically tied to its developer, Dartmoor Softworks GmbH & Co. KG, and the cultural ecosystem from which it emerged. Founded in Germany, a nation with a deep, resonant history of complex board game (Brettspiel) culture, Dartmoor represented a wave of studios focused on adapting this rich analog library for the PC. The studio’s portfolio, as glimpsed in its MobyGames credits, reveals a pattern: Expedition nach Tikal (another board game adaptation), Rotlicht Tycoon (a more niche tycoon simulation), and later contributions to titles like Command & Conquer: Tiberium Alliances. This is not a studio chasing trends but one anchored in specific genres, particularly the translation of intricate tabletop experiences.

The project’s vision was helmed by key figures: Michael Schacht, the original board game’s author, served as “Author,” ensuring mechanical fidelity. CEO and Producer Klaus Starke and Project Manager Bodo Thevissen provided the operational backbone, with conception also involving Stefan Schraut. The programming was handled by Stefan Schraut and AI by Alexander Jost, with engine programming sub-contracted to L39 Studios—a common practice for smaller studios needing robust 3D isometric capabilities. Art was provided by Jan Wawrzik and Paul Kramer, while sound design and music were the work of Areak Rejda, with voice production by Tina Jobst and overseen by Thevissen.

Technologically, 2004 was a year of transition. The game’s specification as a “CD-ROM” title for Windows, with support for “Keyboard, Mouse” and “Internet, LAN” multiplayer for 2-5 players, places it firmly in the pre-Steam, physical-distribution era. Its “Isometric” visual style and “Board game” gameplay tag indicate a deliberate choice to replicate the tabletop view, prioritizing clarity of state over cinematic 3D. The constraints were those of the mid-2000s PC: accessible hardware, the dominance of DirectX 7/8-era graphics, and the nascent but growing culture of online multiplayer through LAN parties and early internet services. Dartmoor was not pushing technical boundaries but was instead focused on creating a stable, faithful digital counterpart to a physical game. The gaming landscape was saturated with strategy titles, from the real-time behemoths like Warcraft III to the turn-based 4X stalwarts like Civilization III. Web of Power entered this market not as a competitor, but as a curator—a digital museum piece for a specific style of European strategy.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Mechanics of Piety and Power

Web of Power presents a narrative framework that is skeletal yet potent, a scaffold upon which its strategic gameplay is hung. The official description is succinct: “the player steps into the leader of a religious order in medieval times, expanding his influence by building cloisters and sending councils throughout Europe.” This is not a story-driven game with dialogue trees, character arcs, or scripted campaigns. Instead, its “narrative” is emergent, generated entirely through player action within a systemic simulation of medieval ecclesiastical power dynamics.

The core thematic tension is between spiritual benevolence and secular power. The player is not a king or a warlord but an “Abbot” or religious leader. The primary verbs—”building cloisters” and “sending councils”—are acts of establishment and delegation. Cloisters represent permanent footholds of faith and learning, while councils are mobile agents of influence. This mirrors the historical role of monastic orders like the Cistercians or Franciscans, who often operated as transnational networks, wielding soft power through land development, literacy, and papal connections. The expansion set, “The Vatican,” explicitly deepens this theme, introducing the central authority of the papacy as a key strategic element, suggesting mechanics where players vie for papal favors or must negotiate with the Holy See.

The absence of a traditional plot or defined characters is a design choice, not a deficiency. It aligns the game with the “Eurogame” aesthetic it adapts: theme is atmospheric and justificatory, not experiential. The player is an amorphous player-empire, a faceless institution. The “story” is the arc of your order’s growth across the map, the friction with rival orders, and the consolidation of your network. It is a narrative of administrative dominion, of charters won and land parcels developed. The dialogue, per the credits, is handled by voice talent (Tina Jobst), but without a scripted narrative, this likely manifests as brief, functional unit feedback or event notifications—more akin to a simulation’s UI alerts than dramatic scenes. The underlying theme is thus one of quiet, systemic imperialism: the spread of influence as a form of conquest, where the sword is replaced by the charter and the fortress by the monastery.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Precision of the Isometric Grid

Web of Power is, at its core, a digital implementation of a German-style board game (often called a “Eurogame”). Its systems are therefore characterized by direct translation of physical mechanics into digital form, with an emphasis on clear rules, limited randomness, and strategic planning over tactical chaos.

Core Loop & Objective: The primary loop is turn-based and point-based. Players take sequential turns on an isometric map of medieval Europe, subdivided into regions (likely hexes or provinces). The goal is to accumulate victory points, primarily through controlling regions via your built cloisters and the successful deployment of your council members. The expansion “The Vatican” would introduce additional point avenues and perhaps new mechanics tied to the papal court.

Area Control & Network Building: The central mechanic is area control, but with a twist. Placing a cloister in a region gives you a permanent, passive presence. “Sending councils” is the active phase—moving discrete agent pieces (councils) from your supply into regions, either to contest an opponent’s cloister, support your own, or establish a new one. This creates a dynamic network where control is fluid and requires spatial reasoning. A region is typically controlled by the player with the most “influence,” which is a sum of cloisters and councils present. This incentivizes clustering forces but also spreading thin to claim territory.

Resource Management & Action Points: Most such games use an action-point system. Each turn, a player has a limited pool of actions (e.g., “build cloister,” “move council,” “recruit council”). Larger or more distant actions may cost more. This forces agonizing trade-offs: do I consolidate my position or expand aggressively? Can I afford to both build and move in the same turn? The digital format automates the accounting, a clear advantage over the physical board game.

Interaction & Conflict: Conflict is non-violent and Euro in style. There is no army combat. Instead, “battles” are simple compare-and-contrast: when two players’ councils contest the same region, the one with the greater sum of units wins control, often forcing the loser’s units to retreat. This is deterministic, based on committed forces, eliminating luck-based combat resolution. The tension comes from the commitment of pieces and the predictability of opponent’s possible moves.

Progression & Scaling: Progression is not about individual unit growth but about network expansion. As the game progresses, the board fills, and regional control becomes more contested. The late game is about securing key regions that grant disproportionate points or locking down areas to prevent opponent gains. Player elimination is unlikely; scores are tallied at a set number of rounds or when a condition is met.

Innovations & Flaws in Digital Translation: The digital version’s innovations are purely practical: automated rule enforcement, hidden point tracking, seamless multiplayer over LAN/Internet, and a clean isometric UI. These eliminate tabletop chores. However, it likely inherits the board game’s potential flaws: limited randomness (which can make games feel scripted if a player falls behind early), and a potential lack of dramatic comeback mechanics. A significant flaw in any digital board game adaptation is the absence of the tactile, social experience. The game provides none of the table talk, the physical piece-moving satisfaction, or the shared visual space of a board. It is a sterile, rules-optimized simulation. The AI, credited to Alexander Jost, would be a critical factor for solo players. Given the deterministic, combinatorial nature of Eurogames, a competent AI is achievable, but a poor one would render single-player unchallenging.

UI and Accessibility: The UI must clearly show region control, unit counts, and available actions. The isometric perspective aids visibility. The game’s success hinges on this clarity. The source does not critique the UI, but for a game of this complexity, a convoluted interface would be fatal. Its existence on MobyGames with only three collectors suggests it did not achieve widespread adoption, possibly due to niche appeal, marketing, or usability hurdles.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Evoking a Gritty, Institutional Middle Ages

The aesthetic of Web of Power is defined by necessity and genre convention. The isometric 3D engine, likely a modified or licensed middleware (given L39 Studios’ involvement), would render a stylized, functional map of medieval Europe. We can infer an art direction focused on readability: regions must be distinct, cloisters and councils visually clear at a glance. The palette would be earthy—browns, greens, muted blues—evoking a pre-Renaissance, monastic aesthetic. This is not a world of gleaming plate armor or fantastical beasts, but of timbered monasteries, rolling farmlands, and walled towns. The “board game” tag suggests the art might be somewhat illustrative and iconographic rather than striving for realism or grandeur.

Sound design, credited to Areak Rejda, would be utilitarian. Expect ambient loops for different region types (forest, plains, coast), subtle UI clicks, and perhaps low, Gregorian-style chants or simple medieval instrumentation to underscore the religious theme. Voice work (Tina Jobst) would be minimal, likely restricted to event announcements (“The Pope grants you a blessing…”) or unit acknowledgments. The goal is atmosphere without distraction, reinforcing the game’s contemplative, strategic pace rather than its excitement.

Together, these elements create a world that is less a “place” and more a strategic diagram. It evokes the institutional, land-based power of medieval religious orders—a world of endowments, farms, and political maneuvering, not of knights errant or dragon hoards. The atmosphere is one of quiet, pervasive influence. The lack of a strong narrative or cinematic presentation means the world-building is purely environmental and mechanical, a successful translation if the map feels like a coherent, contestable space for institutional growth.

Reception & Legacy: The Obscurity of the Faithful Adaptation

Web of Power exists in a curious reception void. On MobyGames, it has a Moby Score of “n/a,” is “Collected By” only 3 players, and has no critic or player reviews. This is not an anomaly for its niche category. Its commercial launch was undoubtedly modest, likely limited to German-speaking markets initially (given its alternate title Kardinal & König and publisher Russobit-M’s regional focus) before a wider, quiet European release.

Its critical reception, therefore, must be inferred. In the board game adaptation space, reviews often hinge on two axes: fidelity to the source material and quality of the digital implementation. For those who cherished the original Michael Schacht board game, Web of Power was almost certainly praised for its accurate ruleset and clean presentation. It would have been seen as a valuable tool for remote play and solo practice. However, for the broader strategy gaming audience, its lack of flash, its niche theme, and its deterministic, low-luck mechanics might have made it seem dry, slow, or unexciting compared to the era’s real-time and narrative-heavy strategies.

Its legacy is one of preservation and obscurity. It did not spawn sequels or significantly influence mainstream game design. Its influence is contained within the subculture of digital board game adaptations. It stands as a peer to titles like Catan computer versions or Ticket to Ride adaptations, but one that lacked the brand power or marketing push of those titles. The inclusion of “The Vatican” expansion from the start shows an understanding of the board game community’s desire for completeness, a hallmark of dedicated adaptations.

The game’s true historical value is as a case study. It demonstrates the challenges of translating a thinky, abstract Eurogame to a medium that often rewards immediacy and visceral feedback. It highlights the work of Dartmoor Softworks, a studio that operated with a clear, focused vision for a specific audience. Its obscurity is a reminder of the vast graveyard of competent, niche games that serve their community perfectly but vanish from the broader consciousness. It is a footnote, but a well-executed one, in the history of bridging tabletop and digital play.

Conclusion: A Niche Masterpiece of Systemic Purity

Web of Power is not a lost classic waiting to be rediscovered by the masses. It is, instead, a perfectly preserved artifact of a specific design philosophy: the belief that the essence of a great board game lies in its elegant, interlocking systems, and that a digital adaptation’s highest calling is to replicate those systems with perfect fidelity and convenient automation. Developed by a specialist studio at a time when such adaptations were gaining a dedicated but small following, it succeeds in its primary mission. The mechanics of building cloisters and maneuvering councils are implemented with clean precision. The isometric view serves the gameplay. The multiplayer support fulfills the board game’s social promise.

Its weaknesses are the weaknesses of its genre and source: a dearth of traditional narrative, an aesthetic prioritizes function over flourish, and a strategic pace that demands patience. Its obscurity is earned not through failure, but through a focused target audience that, while dedicated, is small. For the historian, Web of Power is invaluable. It is a clear, unadorned look at the German-style board game adaptation ethos of the early 2000s. It shows a studio (Dartmoor Softworks) working within its means to honor a designer’s vision (Michael Schacht’s). It is a game that understands its purpose: to let players engage with the intricate politics of medieval ecclesiastical expansion, not through character or story, but through the satisfying placement of wooden-meeple analogs on a digital map. In the vast library of video game history, it is a quiet, well-made niche title—a testament to the fact that not every game needs to be a blockbuster to be a perfectly functional, historically significant piece of the medium’s mosaic. Its place is secure among the cult classics of digital board gaming, a faithful digital echo of a clever tabletop design.