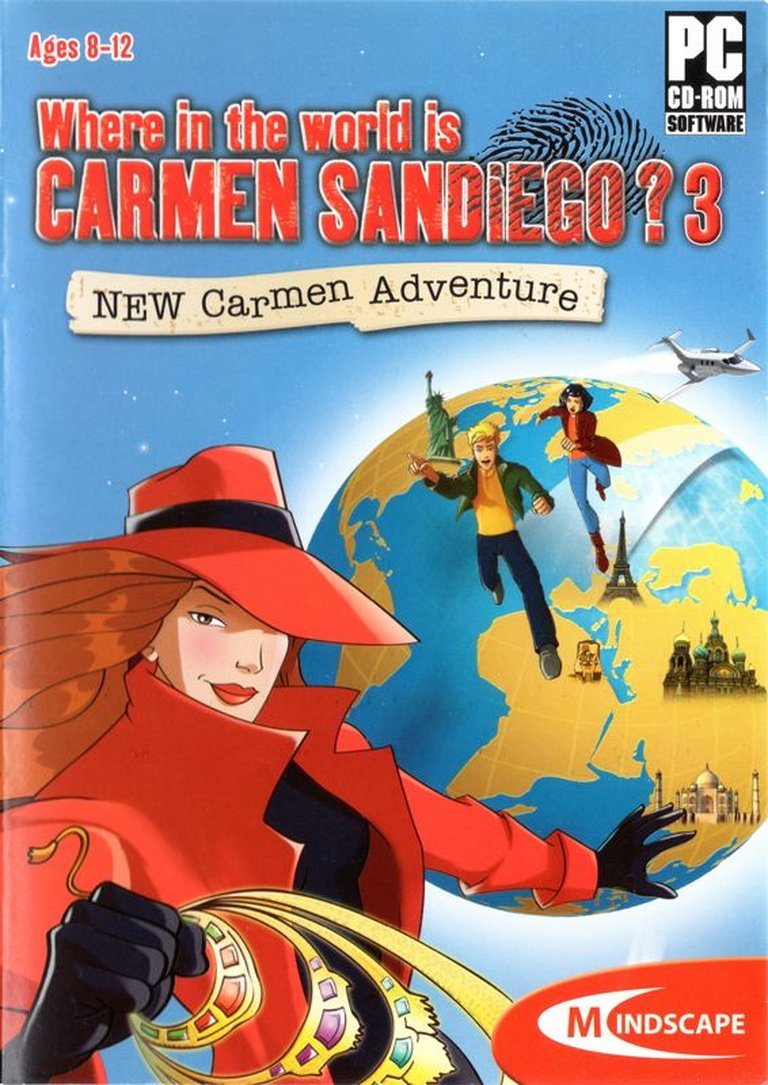

- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Nintendo DS, Windows

- Publisher: Mindscape Asia Pacific Pty Ltd., Mindscape France

- Developer: Strass Productions

- Genre: Educational, Puzzle

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Dialogue, Point-and-click, Puzzle

- Setting: Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, South America

- Average Score: 35/100

Description

Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? 3 is an educational adventure game in the long-running Carmen Sandiego series, targeted at children aged 8-12, where players team up with A.C.M.E. agents Julia Argent and Adam Shadow to track the elusive thief Carmen Sandiego across diverse global settings including Tokyo, Machu Picchu, and the German countryside. Shifting from classic clue-based globetrotting to puzzle-focused gameplay, it features a linear detective story with point-and-click mechanics, dialogue options, a handheld ACME computer for gadgets, and a world map for navigation, emphasizing geography education through mysteries set in continents like Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America.

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (45/100): tired, uninspired and buggy

Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? 3: Review

Introduction

In the annals of educational gaming, few franchises have captured the imagination of young minds quite like Carmen Sandiego, a series that transformed globetrotting detective work into an interactive lesson on geography, history, and culture. Debuting in 1985 as a simple Apple II title, the series evolved from clue-chasing simulations to multimedia adventures, teaching millions while entertaining with its elusive master thief. Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? 3, released in 2008 for Nintendo DS and 2009 for Windows, represents a late-era entry in this storied lineage—one that promised to reinvigorate the formula for a new generation of digital sleuths aged 8 to 12. Yet, as we’ll explore, this French-developed puzzle adventure stumbles where its predecessors soared, offering a linear, puzzle-driven chase that prioritizes point-and-click simplicity over the open-ended discovery that defined the series. My thesis: While Carmen Sandiego 3 valiantly attempts to modernize the brand with portable tech and a global mystery, its overly directive design, shallow educational content, and technical shortcomings render it a disappointing footnote in a franchise that once redefined edutainment.

Development History & Context

The development of Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? 3 unfolded against the backdrop of a shifting educational gaming landscape in the late 2000s, where portable devices like the Nintendo DS were revolutionizing accessibility for young players, and publishers sought to revive aging IPs amid a surge of casual and mobile titles. Spearheaded by Paris-based Strass Productions—a modest studio known for family-friendly fare like Army Defender and Cuisine Party—the game was conceived under the guidance of game concept and storyline creators Jérôme Erbin and Ève Sarradet. Strass, with its small team of 41 developers (plus six additional thanks in credits), emphasized a point-and-click structure tailored for children, drawing from the series’ detective roots but shifting away from the open-world clue-gathering of earlier entries.

Publisher Mindscape France, a subsidiary of the larger Mindscape entity (itself acquired by The Learning Company in the late 1990s, which had absorbed Broderbund—the original Carmen stewards), handled distribution across Europe and Asia-Pacific. This corporate lineage is telling: By 2008, the Carmen IP had passed through multiple hands, from Broderbund’s innovative 1980s simulations to The Learning Company’s CD-ROM expansions in the ’90s and early 2000s. Mindscape’s vision, as inferred from credits like Executive Vice-President of Kid’s Games Pierre Raiman and International Executive Producer Béatrice Jeannès, aimed to leverage the DS’s dual-screen and touch capabilities for an “e-learning” experience. However, technological constraints loomed large; the DS’s limited processing power favored fixed-screen visuals and simple menus over dynamic 3D worlds, resulting in a hybrid of 2D illustrations and static slides. The era’s gaming market was dominated by high-octane blockbusters like Super Mario Galaxy and Grand Theft Auto IV, making Carmen 3‘s educational focus feel niche—yet it arrived just as iOS apps were emerging to fragment the edutainment space. Localization efforts, managed by Georges Martins, ensured releases in French (Mais où se cache Carmen Sandiego?: Mystère au bout du monde) and German (Wo auf der Welt ist Carmen Sandiego?: Das Geheimnis am Ende der Welt), but the core vision remained a linear adventure, perhaps constrained by budget and the need to appeal to a post-NCLB (No Child Left Behind) emphasis on measurable learning outcomes. Ultimately, Strass’s modest resources—evident in the 47-person credit list, including illustrators like Anthony Cocain and testers like Florent Chevallier—produced a game that felt more like a safe, puzzle-box iteration than a bold evolution, reflecting the series’ waning momentum after 2004’s The Secret of the Stolen Drums.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its heart, Carmen Sandiego 3 adheres to the franchise’s detective-mystery narrative, but it condenses the sprawling, player-driven hunts of yore into a tightly scripted tale of international intrigue. The plot kicks off in ACME’s New York headquarters, where the Chief briefs Agent Julia Argent on a rash of high-profile thefts: treasures from across the globe, including artifacts from Tokyo, Machu Picchu, the German countryside, France, Egypt, Peru, and beyond. Suspecting Carmen Sandiego’s V.I.L.E. operatives but lacking hard evidence, Julia teams up with Adam Shadow (a reimagined version of the series’ tech-savvy Shadow Hawkins) to recover the items before public panic ensues. Technical whiz Matt Forrest provides remote support, adding a layer of gadgetry to the proceedings.

As the duo jet-sets via an interactive world map—spanning Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America—the narrative unfolds linearly across 10 countries. Players piece together clues through dialogues and puzzles, culminating in a twist: Carmen has been eavesdropping on ACME communications, orchestrating the heists to lure agents into assembling a digital map of the lost city of Atlantis. In a climactic reveal, Carmen swipes the map and flees to South America, leaving Julia and Adam one step behind. This meta-layer—echoing Carmen’s canonical cleverness—touches on themes of deception, global interconnectedness, and the thrill of the chase, but it’s undermined by the story’s brevity (a mere two hours) and overt hand-holding.

Characters are archetypal but underdeveloped: Julia embodies the determined female protagonist (a nod to the series’ progressive roots, with Lauren Elliott’s influence from earlier games lingering in spirit), while Adam offers comic relief as the reformed hacker. Carmen herself remains elusive, appearing in taunting cutscenes that highlight her as a stylish anti-heroine—red coat billowing, voice dripping with sarcasm. Dialogue options, a staple of point-and-click adventures, allow branching conversations with locals (e.g., querying Egyptian guides on ancient lore or Peruvian historians on Incan sites), but choices rarely impact outcomes, reducing agency to illusion. Thematically, the game nods to cultural education—glimpsing Tokyo’s neon bustle or Germany’s pastoral charm—but it’s superficial, more postcard than deep dive. Underlying motifs of cultural preservation (stolen treasures as metaphors for lost heritage) clash with the plot’s Atlantis fantasy, creating a tonal inconsistency. In extreme detail, the narrative’s linearity strips away the series’ empowerment of young players as junior detectives; instead of piecing together a web of clues to corner Carmen, you’re funneled toward predetermined revelations, diluting the intellectual thrill that made predecessors like Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? (1985) enduring classics.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Carmen Sandiego 3 pivots from the series’ traditional clue-based globetrotting to a puzzle-centric point-and-click loop, designed for touch-screen simplicity on DS and mouse-driven ease on PC. Core gameplay revolves around a linear progression: Select a destination on the world map (a static, zoomable interface highlighting continents like Africa for Egyptian locales or South America for Machu Picchu), arrive at fixed/flip-screen scenes, engage in menu-driven interactions, and solve puzzles to advance the story. The ACME handheld computer serves as a central hub—scanning environments for clues, analyzing items (e.g., decoding a German cipher or mapping Peruvian ruins), and tracking progress toward higher ranks upon case completion.

Puzzles form the backbone, blending inventory management with environmental challenges: Combine a stolen artifact with a digital scanner to reveal hidden data, or select dialogue paths to extract info from NPCs without failing (though failure is rare, thanks to hints). No combat exists—true to the series’ non-violent ethos—but progression feels directive, with “ultra-dirigiste” paths (as French critics noted) that telegraph solutions via glowing prompts or auto-suggestions. The UI is clean yet basic: Dual-screen DS layout splits map/inventory on top and interaction below, while PC uses pop-up menus. Innovative touches include touch-based dragging for puzzle assembly (e.g., fitting Atlantis map fragments), but flaws abound—repetitive loops of “talk-investigate-puzzle-travel” grow stale quickly, and bugs like game-stopping glitches in scene transitions (reported in reviews) halt momentum.

Character progression is minimal: Ranks rise with solved cases, unlocking minor perks like faster scans, but no skill trees or customization exist, unlike RPG-infused edutainment peers. The system’s brevity (2-4 hours total) amplifies flaws; puzzles lack challenge for anyone over 10, with no lose conditions or replayability beyond optional trivia quizzes on geography. Analytically, this represents a flawed evolution: By ditching open-ended clue hunts for scripted puzzles, the game sacrifices replay value and educational depth, turning a series once praised for fostering curiosity into a rote checklist. For its era, the portable format was forward-thinking, but without robust systems to engage young players, it feels like a missed opportunity amid DS hits like Professor Layton.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world-building spans a diverse tapestry of 10 countries, from New York’s ACME HQ to Tokyo’s vibrant streets, Egypt’s pyramids, Germany’s rolling hills, Peru’s ancient sites, and more—evoking the series’ global allure while tying into geography education. Settings contribute to immersion by contextualizing thefts: Steal a Japanese artifact, and you’re thrust into bustling markets; in Peru, Machu Picchu’s ruins frame Incan lore puzzles. This fosters a sense of worldly adventure, with the Atlantis map as a mythical capstone, blending real cultures with speculative history to spark young imaginations.

Visually, the art direction leans on bright, clean 2D illustrations by Anthony Cocain and team, rendered in a fixed/flip-screen style that suits the DS’s constraints. Scenes are colorful and child-friendly—Tokyo’s neon pops against blue skies, Egyptian sands shimmer statically—but the “slide 2D pictures across the screen” approach (per PALGN) feels lifeless, with minimal animation beyond basic transitions. No dynamic lighting or parallax scrolling elevates the atmosphere; instead, it’s a static diorama, pretty yet uninvolving, which undercuts the “mystery at the end of the world” subtitle.

Sound design is sparse and functional: A light orchestral score underscores travels, with ambient noises (market chatter in Asia, wind in the Andes) adding flavor. Voice acting is absent—dialogue is text-only, a cost-saving measure that misses opportunities for charismatic reads like Rockapella’s iconic theme from the TV show. SFX for puzzles (clicks, scans) are crisp but repetitive, and the PEGI 3 rating ensures no jarring elements. Overall, these contribute a cozy, approachable vibe for kids, but the lack of depth—static visuals paired with muted audio—dulls the exploratory thrill, making the world feel more like a brochure than a living mystery.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Carmen Sandiego 3 faced scathing critical reception, averaging 25% on MobyGames from two reviews and unranked elsewhere due to sparse coverage. French outlet Jeuxvideo.com lambasted it as “ultra-dirigiste, peu attractif et court” (overly directive, unattractive, and short), scoring the DS version 30% and Windows 25%, warning nostalgics to steer clear. Pocket Magazine echoed this at 20%, decrying the lack of challenge, linearity, and absent educational meat—ironic for a geography-focused title. English reviews were mixed: PALGN’s 2.5/10 highlighted “indifference,” frustrating puzzles, and bugs; CNet’s 4/10 called it “mediocre” and “unsatisfying,” noting sexual innuendos unfit for kids; yet Impulse Gamer’s 6.9/10 praised it as “sturdy” e-learning amid console violence. Player scores averaged 2.6/5 on MobyGames (four ratings, no reviews), suggesting quiet disappointment. Commercially, it flew under the radar, with limited releases and no major sales data, overshadowed by the 2011 Netflix revival’s groundwork.

Legacy-wise, the game has evolved into a cautionary tale for IP revivals. It influenced little directly—succeeding titles like Carmen Sandiego Adventures in Math (2011) returned to math puzzles—but highlighted edutainment pitfalls: Over-simplification erodes engagement. In the broader industry, it underscores the Carmen franchise’s resilience; post-2009, Google Earth’s Carmen Sandiego Returns (2013) and Netflix’s animated series (2019) reclaimed the brand’s interactive, globe-spanning magic. As a historian, I see Carmen 3 as a low point, emblematic of mid-2000s licensed games that prioritized quick ports over innovation, yet it preserves the series’ core: A thief who teaches us the world, even in flawed form.

Conclusion

Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? 3 embodies the challenges of sustaining a 20+ year legacy in a fast-evolving medium—its earnest global mystery and puzzle mechanics nod to the franchise’s educational heart, but linear scripting, technical bugs, and superficial depth hobble its potential. From Strass Productions’ modest vision to its poor reception, the game serves as a bridge too far, a relic of 2008’s DS era that prioritized accessibility over adventure. In video game history, it earns a middling place: Not a disaster like some forgotten tie-ins, but far from the pantheon of Broderbund’s originals. For parents or educators seeking light geography fun, it’s passable nostalgia bait; for true fans, it’s a reminder of what made Carmen great—unfettered exploration. Verdict: 3/10. Skip unless you’re a completist; the real treasure lies in revisiting the classics or awaiting modern reboots.