Description

In ‘Wik & the Fable of Souls’, players control Wik, a frog-man hero, navigating a fantastical 2D world where they must use his extendable tongue to swing between trees, capture grubs, and deliver them to a slow-moving mule before it wanders off—all while fending off dangerous creatures like flies, bats, and scorpions. The game blends action and puzzle elements through its story mode, which explores a sinister mystery behind the grubs, and a challenge mode that tests skills with advanced acrobatic tricks, all set against atmospheric, hand-drawn environments.

Gameplay Videos

Wik & the Fable of Souls Free Download

Wik & the Fable of Souls Guides & Walkthroughs

Wik & the Fable of Souls Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (77/100): The most innovative game on the xbox live arcade, and it’s filled with gametypes that make it well worth the Microsoft points.

mobygames.com (78/100): Wik and the Fable of Souls wakes memories of the good old arcade days when games were tests of skill taking place within a single screen.

metacritic.com (77/100): Coupled with more exciting levels in the latter stages of the main mode, and the thrill of hitting triple-digit scores in Loopnastics, Wik is like a web-game that grew up.

Wik & the Fable of Souls Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes during gameplay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| cheatunlockall | Unlock all game types/levels |

| togglevsynch | Toggle V-Sync |

| graphfps | Show FPS (graphics version) |

| showfps | Display frame rate |

| showtexturecache1 | Show information about texture memory |

| showtexturecache2 | Show information about texture memory |

Wik & the Fable of Souls: A Cult Classic’s Tangled Tongue and Twisted Tale

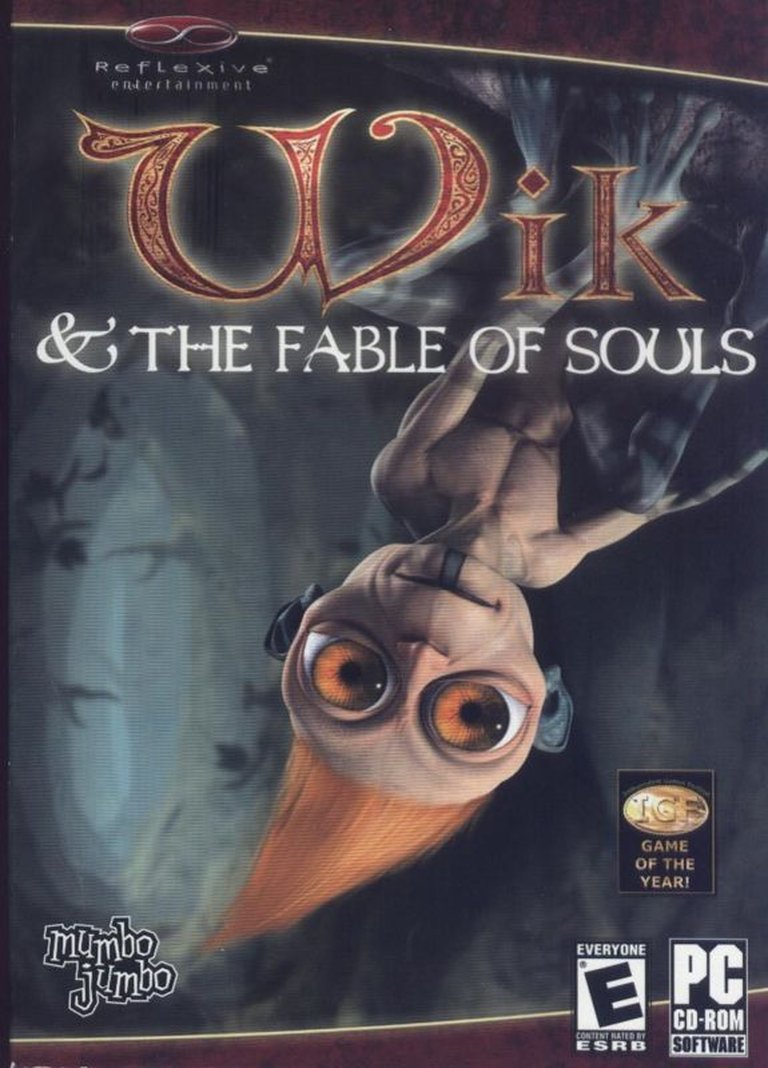

In the annals of mid-2000s digital distribution, few games capture the spirit of independent audacity and design ingenuity quite like Wik & the Fable of Souls. Released at a time when “downloadable games” were often synonymous with simplistic puzzle clones, Reflexive Entertainment’s 2004 title emerged as a darkly whimsical, mechanically profound experience that rewarded dexterity, foresight, and a tolerance for the grotesque. It is a game that beginas a bizarre prototype about geckos and evolves into a poignant fable about loss, parasitism, and the desperate measures of a grieving hero. To play Wik & the Fable of Souls is to engage with a idiosyncratic vision—a game where the central mechanic is not jumping, but swinging, and where the primary objective is herding monstrous larvae toward a patient mule. This review argues that Wik & the Fable of Souls is a landmark of indie game design, a title whose innovative physics-based platforming and deeply unsettling narrative cohere into an experience that, despite its commercial modesty, left an indelible mark on the landscape of digital and console gaming.

1. Introduction: The Frog, the Mule, and the Grubs

In 2004, the downloadable game market was a frontier. Platforms like Reflexive’s own Arcade and the nascent Xbox Live Arcade were proving grounds for ideas too niche or risky for retail. Into this space stepped Wik & the Fable of Souls, a game that immediately distinguished itself through its bizarre protagonist and core loop. You are Wik, a frog-like “forest dweller” with an extendable, adhesive tongue. Your companion is Slotham, a docile, slow-moving mule-like creature. Your task? To rescue “baby grubs”—glowing, eyed larvae—from a menagerie of hostile insects and deliver them to Slotham’s magical backpack before he ambles off-screen. The twist? The grubs are horrifically parasitic; their hypnotic gaze compels creatures to nurture them, only for the grub to eventually absorb its host and emerge as a monstrous adult. Wik’s mission is a perverse act of mercy: collecting them to prevent another cycle of death and destruction, a cycle that claimed his own family.

The thesis of this analysis is that Wik & the Fable of Souls succeeds as a masterpiece of integrated design. Its genius lies in how its singularly strange gameplay mechanic—a tongue that both swings and spits—directly embodies its themes of control, predation, and fragile salvation. Furthermore, its development history, marked by a dramatic mid-stream mechanical revolution, is a classic case study in indie resilience and creative pivot. While its narrative delivery is fragmented and its commercial reach limited, its core loop remains one of the most satisfying and physically expressive in 2D platforming history.

2. Development History & Context: From BugEater to Fable

Wik & the Fable of Souls was developed by Reflexive Entertainment, a California-based studio founded in 1997. By the early 2000s, Reflexive had a foot in both traditional PC publishing (titles like Lionheart: Legacy of the Crusader) and the burgeoning world of casual, downloadable games via their “Reflexive Arcade” portal. The project originated from what the studio called a “one-day-quick” prototype named “BugEater”, created by programmer James C. Smith. Inspired by Missile Command, the original concept was a chaotic multiplayer experience: players controlled multiple geckos on screen borders, clicking to make them jump and eat bugs threatening grubs. Played with a “MouseParty™” of eight people around one PC, it was a click-frenzied mayhem that was undeniably fun in that specific context.

The transition to a compelling single-player game, however, was the project’s greatest challenge, a struggle candidly detailed in producer/lead programmer Simon Hallam’s postmortem. For the first three months, the game simply wasn’t fun. The core mechanic of clicking to make Wik jump in a straight line felt flat. Attempts to add depth—obstacles, auto-grabbing, a complex “dynamic stinky cheese” particle system to lure grubs—failed to create a sustainable gameplay loop. The “stinky cheese,” a computationally expensive fluid dynamics simulation, was a dead end that consumed resources without delivering fun.

The monumental turning point came from programmer Brian “physics guru” Fisher: the introduction of gravity. Suddenly, Wik’s movement had weight and momentum. Crucially, the team experimented with allowing Wik’s tongue to latch onto surfaces mid-jump, enabling him to dangle and swing. “It was immediately apparent that we had hit upon something special,” Hallam wrote. This was the spark. The decision to scrap all existing level design and rebuild the game around jump-and-swing mechanics was a huge risk given a compressed six-month development cycle and a tight 15MB download size limit, but it was non-negotiable. The new physics created a skill ceiling—players could learn to control swing momentum for precise traversal—and an inherent tension, as a mistimed release meant a fall into scorpion pits.

This pivot defines the game’s legacy. It exemplifies the indie ethos of following the fun, even if it means discarding months of work. The resulting toolchain—a prop-based level editor and a “Wik style sheet” with 86 tunable parameters—was a direct response to this chaotic rebirth, allowing designers and artists to rapidly iterate on levels now built for a swinging protagonist. The mouse-only control scheme was another deliberate design choice to lower the barrier to entry for the casual download market, though as critic Kit Simmons noted, this led to a control model with deceptive depth: the game performed “internal calculation and prediction” to make Wik feel responsive, often modifying literal cursor input to prevent frustrating falls and ensure successful tongue latches.

What Went Wrong: The postmortem is brutally honest. The biggest failure was the initial faith in the “BugEater” prototype’s single-player viability, a blind spot born of successful multiplayer testing. Producer Hallam admits he never fully believed in the original mechanic, creating a dangerous gap between vision and execution. Other cuts were painful: planned boss battles (a Hornet Queen, a Spider Boss) were modeled and animated but scrapped for time, their chase mechanics rendered obsolete by the new gravity-based movement. Finally, a post-release OpenGL compatibility issue affected 8-12% of users due to driver update quirks; the team ultimately had to implement a software rasterizer to ensure broader accessibility, sacrificing some particle effects in the process.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Fairy Tale of Parasites and Grief

Wik & the Fable of Souls presents a narrative that is surprisingly dense for a 15MB casual game, told entirely through evocative, poem-like verses at the start of each level set. Written by Eric Dallaire, the story is a dark fairy tale, a thematic core that perfectly complements the grotesque gameplay.

The grubs are not merely pests; they are biological horror. Their lifecycle is one of parasitic compelled nurturing: a grub’s hypnotic antenna forces a creature to bring it home, where it implants itself, steals the host’s life, chrysalizes, and hatches as a monstrous adult that rampages back to its origin point. The “sinister mystery” hinted at in official descriptions is this horrific cycle. Wik’s tragedy is personal: his family was killed by transformed grubs during the last “mass communal birthing.” His mission is not heroic rescue but preventative quarantine. He intends to collect all the scattered grubs and return them to their native land to restore their “cyclical cannibalism”—to have them eat each other instead of innocent hosts. This is a plan born of profound grief and a desire to break a cycle of loss, making Wik a tragic, morally ambiguous figure, not a clean-cut hero.

The narrative deepens with the reveal that the grubs’ own previous generation betrayed their offspring, scattering them to avoid being hosts. This adds a layer of generational sin. Wik’s final confrontation is with the “Lord of the Grubs,” the ultimate guardian of their origin, implying a larger, almost cosmic horror he is trying to contain.

Thematically, the game explores:

* Control vs. Chaos: Wik’s tongue is a tool of precise control in a world of chaotic, hypnotic grubs and swooping predators.

* Burdens of Care: Herding the grubs is a tedious, dangerous task, mirroring the exhausting labor of caretaking.

* Grief as Motivation: Wik’s entire quest is a monument to loss, a desperate attempt to impose order on a universe that took his family.

* The Horror of the Mundane: The cutest creatures (grubs) are the most monstrous, and the slowest (Slotham) is the most vital.

Where the narrative falters is in its delivery. As Simmons’ player review criticizes, the story exists as static text screens before level sets. Wik himself has no personality beyond his abilities; there are no voice lines, no expressive animations during narrative beats. The incredible darkness of the tale is told, not shown, relying on the player’s imagination to connect the poetic text to the grotesque, gleeful action of spitting grubs at bats. It’s a narrative told on a Post-it note attached to a masterpiece of physical gameplay—potent, but clearly secondary to the mechanical experience.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Physics of Salvation

The genius of Wik & the Fable of Souls is its elegant, physics-driven core loop that remains engaging across 120+ levels. The control scheme is deceptively simple: the mouse cursor dictates direction. Left-click makes Wik spit or latch his tongue; right-click makes him jump. But within this simplicity lies immense depth.

- Tongue Latching & Swinging: This is the masterstroke. Clicking on any solid, latchable surface (tree branches, rocks, vines) fires Wik’s tongue. If it connects, he begins to swing like a pendulum. Player momentum is key: swinging builds arc, and releasing the tongue at the apex propels Wik forward. This transforms platforming from a series of static jumps into a rhythmic, spatial puzzle. Levels are designed as towering jungles or caverns where players must chain swings, time releases, and use bounce pads to ascend, all while managing a dwindling timer (Slotham’s march).

- Resource Management & Herding: The goal is never to just reach grubs, but to herd them safely to Slotham. Grubs will wander aimlessly, vulnerable to predators. The player must create a safe corridor, often by spitting inedible objects (acorns, rocks, stunned enemies) to block paths or distract foes. This adds a layer of real-time strategy to the platforming.

- Combat Through Spit: Wik’s primary offensive is projectile vomiting. He can collect a single grub or object in his mouth and spit it shotgun-style to knock enemies (flies, bats, scorpions) out of the air or off platforms. This is often the only way to clear a threat, integrating offense directly into the resource-gathering loop.

- Threats & Hazards: Enemies have specific behaviors. Flies dive for grubs; bats are larger, more durable threats; scorpions patrol platforms, killing Wik on contact. Some levels introduce environmental hazards like falling platforms or toxic pools. The escalating challenge comes not just from added enemies, but from level geometry forcing ever more complex swing chains.

- Progression & Modes: The Story Mode is divided into 16 chapters of 8 levels each (128 total on PC, 120+ on XBLA), introducing new environmental twists (caves, vines, darkness). Each level contains three hidden gems (ruby, emerald, diamond); collecting all is required for the “best ending,” encouraging exploration. The Challenge Mode (or “Loopnastics” on XBLA) isolates the swinging mechanic, presenting pure acrobatic puzzles that demand perfect momentum control—a proving ground for mastery.

- UI & Tutorials: The game famously eschewed traditional text tutorials for an adaptive hint system. In early levels, messages and arrows would guide players. The postmortem details the evolution: initial linear tutorials bored skilled players, while some novices still struggled later. The final system offered help only if the player stalled, aiming to respect player autonomy. It was a sophisticated approach for its time, though not perfect.

Flaws are present. The difficulty curve is brutal from the start, a barrier Simmons noted can “turn off” impatient players. The “gem” collection can feel arbitrary, relying on pixel-perfect swings into hidden nooks. The challenge mode, while brilliant, has no online leaderboards on PC (a feature added on XBLA), limiting its competitive lifespan.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Palpable, Grim Atmosphere

Reflexive’s technical constraints (15MB limit, single static screen per level) forced a creative approach to art that resulted in one of the game’s most praised aspects: its atmospheric, hand-crafted beauty. The team, led by Art Director Jeff McAteer, used a technique of composing screens from pre-rendered 2D props. They painted backgrounds in Photoshop from 3D Studio Max models, then created a library of layered, rotatable “props” (branches, rocks, vines, foreground foliage). The in-house level editor allowed designers (Ion Hardie, Ernie Ramirez) to place these props, apply filters, and build 70+ unique-feeling levels from a finite palette. This method created a hand-drawn, storybook aesthetic with depth and texture, avoiding the repetition Simmons feared. The dark, earthy color palette—murky greens, browns, and purples—supports the grim fairytale tone. Animations, especially Wik’s waddle and his long, coiling tongue, are fluid and expressive.

The sound design is equally integral. Ion Hardie created all the effects, which are crisp and satisfying: the thwip of the tongue, the pop of spitting, the electronic zap of hitting a gem. Zach Young’s soundtrack is a highlight, a collection of melancholic, Celtic-tinged melodies with a haunted, music-box quality. It perfectly underscores the game’s dual nature: playful mechanics underpinned by deep sorrow. The main theme is memorable and haunting. As critics noted, it can feel repetitive over long sessions, but its emotional tone never wavers.

Together, these elements create a palpable world. This is not an abstract puzzle arena but a living, creepy forest and dank cave system. You believe in this ecosystem of grubs, flies, and a solitary frog-man on a desperate mission. The atmosphere is what elevates Wik from a clever physics toy to a cohesive, immersive fable.

6. Reception & Legacy: Critical Darling, Commercial Footnote

Upon release, Wik & the Fable of Souls was met with widespread critical acclaim, particularly on PC where it garnered a Metacritic score of 88/100. Reviews consistently praised its unique hook, addictive gameplay, and atmospheric presentation. Game Tunnel gave it a perfect 100%, calling Wik “one of the cooler characters to come around in awhile.” GameSpot’s 9/10 review hailed its “challenging, intelligent gameplay” and “intriguing, fairy-tale presentation.” The most famous accolade was its win of the Seumas McNally Grand Prize at the 2005 Independent Games Festival (IGF), the highest honor for an indie game at the time. It also won “Downloadable Game of the Year” at the 9th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards (now the D.I.C.E. Awards).

Its 2005 Xbox 360 (Xbox Live Arcade) port, titled Wik: The Fable of Souls, also performed well critically (Metacritic 77/100), though with slightly more mixed notes about its higher price point versus PC. Eurogamer (8/10) called it “like a web-game that grew up,” while IGN (7.8/10) noted its “appealing visual style” but a control scheme that required patience.

However, as Simon Hallam’s postmortem starkly admits, commercial performance was modest. In the volatile “try-before-you-buy” downloadable market, standing out was hard. The game’s initial difficulty and quirky premise likely limited its mass appeal. Its presence on Steam (2007-2010) and later on Amazon and Big Fish Games has kept it available for a dedicated niche, but it never achieved the commercial heights of contemporaries like Bejeweled or Trials HD.

Its legacy is therefore one of a critically revered cult classic and a touchstone for innovative control design. It demonstrated that a single, well-executed physics mechanic could anchor a full game. Its influence can be seen in later titles that emphasized momentum and grappling, from elements in the Ratchet & Clank series to indie darlings like Pitfall Planet. It stands as a high-water mark for Reflexive, a studio that continued making successful casual games (Airport Mania, Big Kahuna Reef) but never again reached this pinnacle of auteur-driven design. For students of game design, the “BugEater” to Wik pivot is a mandatory case study in finding the fun, and in the postmortem’s central lesson: the lead must own the core concept 100%.

7. Conclusion: A Tangled Triumph

Wik & the Fable of Souls is a game of beautiful contradictions. It is a casual game with a hardcore soul, a fairytale drenched in biological horror, a technical marvel built on a repurposed multiplayer prototype. Its legacy is secured not by sales figures but by the purity of its central fantasy: the visceral, pendular thrill of swinging through a meticulously crafted world with a single, sticky appendage. The act of latching onto a vine, building momentum, and launching yourself over a chasm while spitting a rock at a bat is a uniquely satisfying expression of spatial reasoning and timing.

Its flaws are evident: a narrative told in prose rather than performance, a difficulty curve that acts as a gatekeeper, and a lack of traditional “boss” encounters. Yet, these do not diminish its core achievement. In an era increasingly dominated by bloated AAA production and homogenized mechanics, Wik & the Fable of Souls remains a potent reminder that profound gameplay can emerge from a single, bizarre idea nurtured through iterative courage. It is a game that understands its mechanics are its message: control is precarious, momentum must be earned, and sometimes, to save a world, you must first become intimately familiar with the physics of a frog’s tongue.

Final Verdict: A foundational indie masterpiece. Its innovative swing mechanic remains a benchmark for 2D platforming, its atmosphere is hauntingly unique, and its development story is a testament to following the fun. It is an essential, if overlooked, artifact of the mid-2000s indie explosion and a timeless lesson in game design alchemy. 9/10 – A flawed, fantastic fable that swings between genius and frustration, never losing its grip.