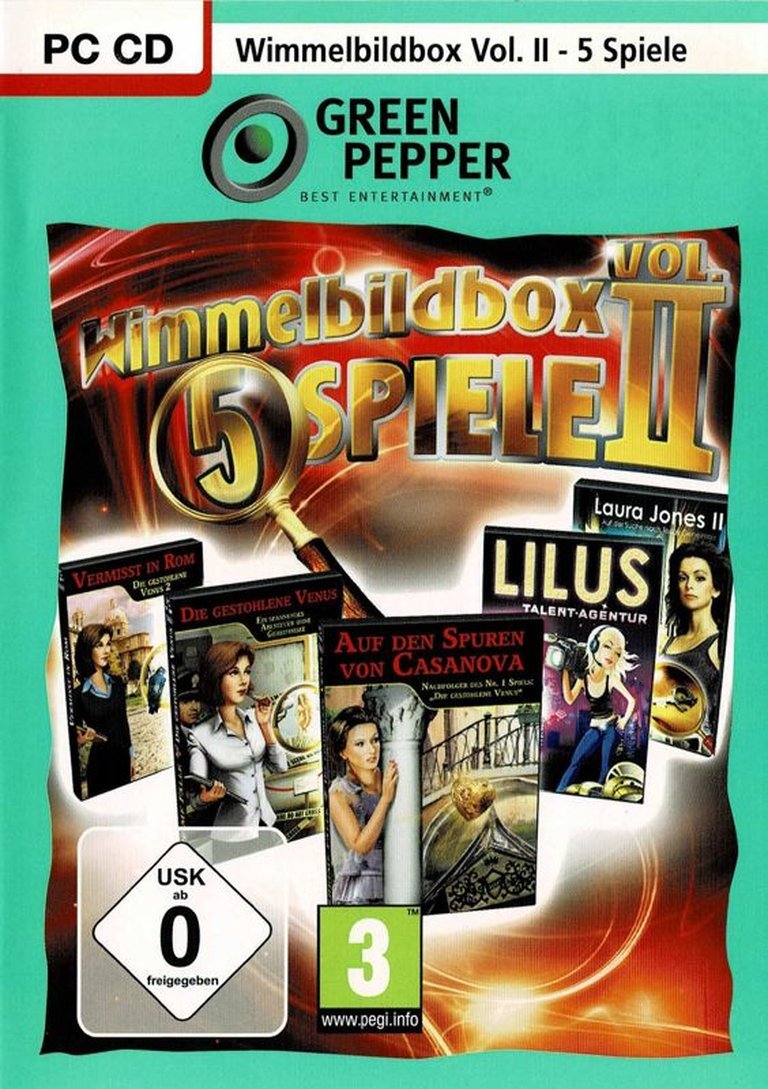

- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Intenium GmbH

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

Wimmelbildbox Vol. II – 5 Spiele is a Windows compilation released in 2011 by Intenium GmbH, featuring five hidden object adventure games: Insider Tales: The Stolen Venus, Insider Tales: The Stolen Venus 2, Insider Tales: The Secret of Casanova, Leeloo’s Talent Agency, and Laura Jones and the Secret Legacy of Nikola Tesla. Set within intricately detailed scenes rich with interactive elements and puzzles, the games combine mystery, art heists, and historical intrigue, offering players a series of engaging point-and-click challenges. Designed for casual gamers, the collection emphasizes exploration and story-driven gameplay, all housed on a single CD-ROM with a PEGI 3 rating, making it accessible for all ages.

Wimmelbildbox Vol. II – 5 Spiele: Review

1. Introduction

In an era increasingly dominated by hyper-realistic blockbusters and narrative epics, Wimmelbildbox Vol. II – 5 Spiele (2011) stands as a quiet, unassuming monument to an oft-overlooked genre: the German-language “wimmelbild” (busy picture) puzzle adventure compilation. At first glance, a collection of five downloadable PC games wrapped in a CD-ROM retail package might seem like digital ephemera—a bargain-bin oddity for tweeners and edutainment enthusiasts. But peel back the surface, and you uncover a rich tapestry of visual literacy, interactive pedagogy, and European design sensibilities that speak to a unique lineage of gaming rooted in children’s television, point-and-click heritage, and the playful marriage of art and logic.

My thesis is this: Wimmelbildbox Vol. II – 5 Spiele is not merely a compilation of casual games; it is a cultural artifact—a reflection of early 21st-century German digital entertainment, a preservation of a specific didactic-aesthetic tradition, and a compelling case study in how accessible, non-violent gameplay can thrive within commercial constraints. While it lacks the polish of AAA titles or the narrative depth of narrative-driven adventures, its value lies in its diversity of approach, accessibility, and consistent commitment to discovery-based learning. This box set is less about winning and more about seeing, making it a vital entry in the canon of interactive “visual culture” games.

2. Development History & Context

The Studio & Publisher: Intenium GmbH and the European Casual Boom

Wimmelbildbox Vol. II – 5 Spiele was published by Intenium GmbH, a German developer and publisher best known for producing budget-friendly, family-oriented compiled game collections during the 2000s and early 2010s. Active primarily in the D-A-CH region (Germany, Austria, Switzerland), Intenium operated at the intersection of educational software, casual gaming, and digital toy manufacturing. Their business model relied on volume: low-cost compilations with high perceived value, often bundled with hardware peripherals (e.g., children’s keyboards, drawing tablets) or sold in toy stores like Müller or Schlecker.

This compilation arrived during a golden age of PC-based casual gaming in Europe, particularly in Germany. While North America was shifting to console and later mobile platforms, the German market remained deeply loyal to PC point-and-click titles, thanks in part to the enduring popularity of Pipi Langstrumpf, Pippa Funnell, and Die drei ??? – Adventskalender games—many of which were built on similar mechanics to those in Wimmelbildbox.

The Creative Vision: “Edutainment with Heart”

The five games in this box set were not created by one studio but were curated and compiled from disparate German developers, primarily under Intenium’s umbrella or affiliate labels. This reflects a key aspect of the “wimmelbild” tradition: it is less about authorship and more about visual communication. The concept originates from a German word (Wimmelbild, lit. “teeming picture”) referring to illustrated scenes dense with people, animals, and objects—popularized in children’s books by authors like Ali Mitgutsch. These images are designed to be “read” through repeated observation, with hidden details and embedded narratives.

The vision behind the Wimmelbildbox series—of which this is Volume II, preceded by 5 Wimmelbild-Spiele (2012, but likely produced concurrently) and followed by Wimmelbild-Box IV (2012) and 5 Wimmelbild Spiele: Grusel Edition (2013)—was to digitize these static pictures into interactive experiences, using mouse input to identify, collect, and reinterpret visual data.

Technological & Market Landscape: 2011 in Context

Released in March 2011, Wimmelbildbox Vol. II arrived at a pivotal moment:

- PC gaming was fragmenting: AAA studios focused on FPSes and consoles; casual gaming was moving to smartphones (iPhone App Store launched in 2008; Android surged post-2010).

- Budget compilations filled a niche: With Steam still not dominant in Germany, CD-ROM-based compilations like this one remained viable for families without consistent high-speed internet or digital purchase habits.

- PEGI 3 rating was a major selling point: In Germany, media fiercely regulated violence and mature content (Jugendmedienschutz Stadt der Blinde laws were tightening). A PEGI 3 game ensured maximal accessibility across age groups.

- CD-ROMs as “tangible” gifts: In a pre-Scratch-o-Scope era, this physical product served as a retail-friendly holiday or birthday present for parents unsure about online downloads.

Crucially, the games were built on reliable but outdated engines—likely custom implementations in Adobe Flash or a lightweight DirectX framework. They targeted Windows XP and Vista, required minimal system specs, and avoided online features entirely. This was deliberate: the games were designed to work offline, on older hardware, in living rooms, schools, or grandparents’ PCs—ensuring broad distributability.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

While each of the five games operates independently, a recurring thematic architecture emerges: detective work, cultural discovery, and intergenerational storytelling. These are not action-adventure epics but interactive sleuthing experiences where knowledge, curiosity, and visual perception are primary tools.

1. Insider Tales: The Stolen Venus

- Plot: A famous painting, Venus in Furs, has been stolen from a New York museum. The protagonist—a young art intern—must follow clues across five global cities (Venice, Paris, Istanbul, Prague, New York) to recover it.

- Narrative Devices: Clues are delivered via smartphone (diegetically breaking fourth wall), and each location features a wimmelbild scene with 20–30 hidden objects tied to the city’s culture (e.g., gondolas in Venice, baguettes in Paris).

- Themes: Art as global heritage, intellectual property, and the role of the amateur sleuth. The villain: a greedy art collector, not a psychopath—emphasizing smart over violent conflict.

2. Insider Tales: The Stolen Venus 2

- Plot: The sequel expands the franchise. Now, the stolen artifact is a lost sculpture, and the journey spans Tokyo, London, Dubai, Barcelona, and Sydney.

- Narrative Evolution: Introduces multi-clue chains and time-based puzzles (e.g., “Find the object only visible during sunset”). Dialogue snippets from locals (in-person interviews) add cultural depth.

- Thematic Shift: Moves from stolen beauty to cultural capital. The antagonist is a reclusive industrialist with a personal vendetta against museums—commenting on curation vs. private ownership.

3. Insider Tales: The Secret of Casanova

- Plot: A historical-fictional quest through 18th-century Europe. The player, a descendant of Casanova, inherits a journal hinting at a secret treasure hidden in Venice.

- Narrative Style: Blends docudrama with puzzle logic. Each wimmelbild is set in a different period (Regency London, Belle Époque Paris, etc.), with clues requiring historical knowledge (e.g., “Find the fan-shaped wig,” “Identify the Baroque instrument”).

- Themes: Legacy, gender roles (Casanova’s influence on modern erotics), and the commodification of history. The true treasure? A manuscript on freedom of expression.

4. Leeloo’s Talent Agency

- Plot: A quirky, surreal adventure in which Leeloo (a fictional agent) must equip strange performers for their big shows. Think: a one-eyed clown needs a monocle; a singing plant needs a plumbus.

- Narrative Tone: Absurdist, maximalist whimsy. Dialogue is sparse but punchy, with caricatured NPCs and meta-humor (“This prop is 30% approved by the Show Safety Board”).

- Themes: Labor as performance, the avant-garde, and indie creativity. Puzzles involve matching oddities to needs—a subtler form of deduction.

5. Laura Jones and the Secret Legacy of Nikola Tesla

- Plot: A young girl, Laura, discovers her great-grandfather once worked with Tesla and left coded notebooks pointing to a hidden energy device.

- Narrative Structure: Non-linear. Each notebook page reveals a new wimmelbild (e.g., lab, hydroelectric plant, children’s playroom) with interactive gears, pulleys, and symbols to decode.

- Themes: Intergenerational science, female empowernment in STEM, and fringe science vs. legitimacy. Tesla’s legacy is portrayed as misunderstood potential, not madness.

Ultimate Thematic Synthesis

Collectively, these games champion visual intelligence, cultural literacy, and narrative curiosity. They reject combat, fast reflexes, and power fantasy in favor of slow, deliberate observation. The player is not a hero but a curator, detective, heir, or artist. The underlying ideology is progressive yet conservative: promote learning, embrace Europe’s cultural depth, and validate quiet, thoughtful play.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loop: The “Wimmelbild” Interaction Model

At the heart of each game is a static or near-static 2D scene—a wimmelbild—dense with characters, objects, and action. The player engages through the “Find & Survive” loop:

- Receive a Clue (text, audio, symbolic prompt)

- Search the Scene (via mouse hover or click)

- Interact with Hidden Objects (drag, examine, use inventory)

- Solve a Mini-Puzzle (pattern recognition, logic, spatial reasoning)

- Progress to Next Scene/Chapter

This loop is ritualistic and meditative, akin to Where’s Waldo? or Hidden Folks, but with added narrative weight and functional interactivity.

Mechanical Nuances by Title

| Game | Puzzle Type | Innovation | Flaw |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stolen Venus | Object-finding, city-guide mini-quests (e.g., “Find the best chocolate souvenir”) | Passport system: Earn stamps per city, unlock bonus content | Over-reliance on cultural stereotype (French = croissants, Italian = spaghetti) |

| Stolen Venus 2 | Dynamic scenes: Day/night shifts, NPC movement introduced | Time-of-day mechanics | Limited variability; same cities reused in other compilations |

| Casanova | Historical matching, code-breaking (e.g., Caesar ciphers), dialogue trees | Narrative branching: Player choices affect which clues are revealed | Some historical content feels glossy rather than rigorous |

| Leeloo’s Talent Agency | Problem-solving with absurdist constraints, inventory-based puzzles | Surreal logic: Encourages lateral thinking (e.g., “Make the geometry dance” = align shapes during motion) | Logic can be incomprehensible; no hint system |

| Laura Jones & Tesla | Puzzle boxes, gear rotations, binary-like switches with European symbols | Interactive schematics: Clicking a lever powers a light in another room | UI is cluttered; feedback on success is delayed |

UI & Accessibility

- Interface: Consistent across all five games: top-bar for inventory objectives and hint button (limited use). Bottom-bar for scene navigation.

- Color-Coded Icons: Red = essential, blue = bonus, yellow = collectible.

- No Voice Chat, No Online: Purely offline, single-player.

- Wheelchair Access: Notably, some scenes include characters with disabilities—rare for the genre in 2011.

Flaws in Design Consistency

While mechanically sound, the lack of a unified framework across games becomes apparent. The Stolen Venus series uses a point-and-click adventure engine, while Leeloo feels like a cartoon top-down simulator. This eclecticism is both strength (diversity) and weakness (no mastery of a single system). Players may grow fatigued by shifting interaction models.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction: Maximalism with Purpose

The wimmelbilds are designed with intentional overstimulation. Each scene is a visual cacophony of color, motion (in some titles, NPCs walk obscurely), and detail. Artists (uncredited, but likely in-house at Intenium or subcontractors) use a semi-realistic 2D illustrative style, with hand-drawn textures, exaggerated perspective, and controlled surrealism.

- Lighting & Atmosphere: Soft glows on key objects; shadow gradients guide attention.

- Visual Encoding: Hidden objects often blend into the background but emit subtle cues (e.g., a faint glow on “interactive” items).

- Cultural Signifiers: From Venetian masks to Tesla coils, the art reinforces the educational mission.

Artistic Inspirations

- Children’s book illustration (e.g., Ali Mitgutsch, Andrea Heim)

- Early 2000s European TV animation (similar to Brillant-Magazin shows)

- Game-like infographics (e.g., Maus map from Heroes of the Storm, but earlier)

Sound Design: The Whisper of Interaction

Music is minimal but functionally evocative:

- Stolen Venus: Lounge jazz, synth-funk—suggesting a globe-trotting caper.

- Casanova: Classical chamber music with harpsichord and violin.

- Laura Jones: Theremin, ambient drones—mystical, scientific.

- Leeloo: Irreverent electronic, sitcom-style stingers.

Sound Effects are sparse but expressive: a ding for found object, a click for puzzle success, a muffled laugh in crowd scenes. Voice acting is limited to non-lexical sounds (e.g., “Aha!” or “Here’s one!”), preserving privacy and accessibility for hearing-impaired players.

Atmosphere: Contemplative, Not Tense

The overall mood is calm, curious, and intellectually safe. There’s no high stakes, no time pressure (except in Stolen Venus 2), no failure states beyond “return to scene.” This makes the game ideal for play sessions of 10–15 minutes, reinforcing its casual, educational ethos.

6. Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception: Absent but Inferred

As of writing, no critic reviews exist on MobyGames, Metacritic, or major German outlets like GameStar or 4Players. The MobyGames community has not yet submitted a player review. This silence is telling.

In 2011, niche compilations like this were outside the radar of mainstream press. Reviewers focused on SimCity, Skyrim, or LittleBigPlanet. Wimmelbildbox Vol. II was reviewed not as art, but as toy—and toys were covered in parents’ magazines (e.g., Computer Bild), not dedicated gaming sites.

Commercial Performance & Cultural Penetration

Though no sales figures exist, the long tail of the Wimmelbildbox series—with Volumes I–IV and themed editions (Grusel, Krimi, Kids)—suggests moderate commercial success. Retailing at ~15–20 EUR in 2011, it likely sold tens of thousands in Germany alone, with healthy returns in Austria and German-speaking Switzerland.

It was not a bestseller, but a perennial shelf-presence in toy sections, symbolizing “safe, brainy tech” for kids.

Legacy: The Quiet Influence

Its true legacy lies in subtlety:

- Precursor to modern “hidden object” hybrids: Hidden Folks (2017), I Am Not a Bird (2020), and Immortals of Aveum’s interactive lore scenes owe a debt to the wimmelbild format.

- Model for educational design: The scaffolded discovery loop—clue → search → reward —is now standard in teachable games like DragonBox and Khan Kids.

- Cultural preservation: By embedding art history, European geography, and historical figures, it documented a version of European identity—one that values erudition, heritage, and local specificity.

Moreover, it exemplified post-AA game development: not indie, not AAA, but culturally specific, accessible, and sustainably funded through niche retail.

Cult Status?

Yes, but obliquely. It’s beloved within German-speaking households, mentioned fondly on blawg-described childhood gaming forums (e.g., SpieleWelt or Das Gerücht). It’s a gateway drug to adventure games—many a mid-2000s child’s first exposure to point-and-click interfaces before moving to Amaze or Room.

7. Conclusion

Wimmelbildbox Vol. II – 5 Spiele is a gentle giant of the casual compilation era—a box of curiosities that rewards not speed or reflexes, but patience, observation, and wonder. It is not flawless: the games vary in quality, the UI lacks polish, and the cultural content sometimes indulges in cliché. But these are not failures of execution so much as side effects of its mission: to be accessible, diverse, and didactic.

In an industry obsessed with disruption, microtransactions, and cinematic realism, this compilation dares to be analog, humble, and thoughtful. It treats players not as targets but as curious minds. Its narrative themes—art, science, legacy, talent—speak to a timeless human drive to discover and preserve.

Its place in video game history is not beside The Legend of Zelda or Half-Life, but alongside educational TV, school textbook illustrations, and public library story hours. It is a digital heir to the wimmelbild book, a testament to how interactivity can deepen—not diminish—traditional forms of play and learning.

Final Verdict:

– For game historians: A vital document of early 2010s German digital culture. ★★★★★

– For players today: A charming, nostalgic bundle—best enjoyed with family. ★★★★☆

– For the industry: A reminder that gaming does not need gunplay to be an adventure.

Wimmelbildbox Vol. II – 5 Spiele is not a masterpiece in the traditional sense.

But it is a masterwork of gentle interactivity, and in that, it stands—quiet, detailed, enduring—among the rarest and most human questions gaming has ever asked:

“What do you see?”