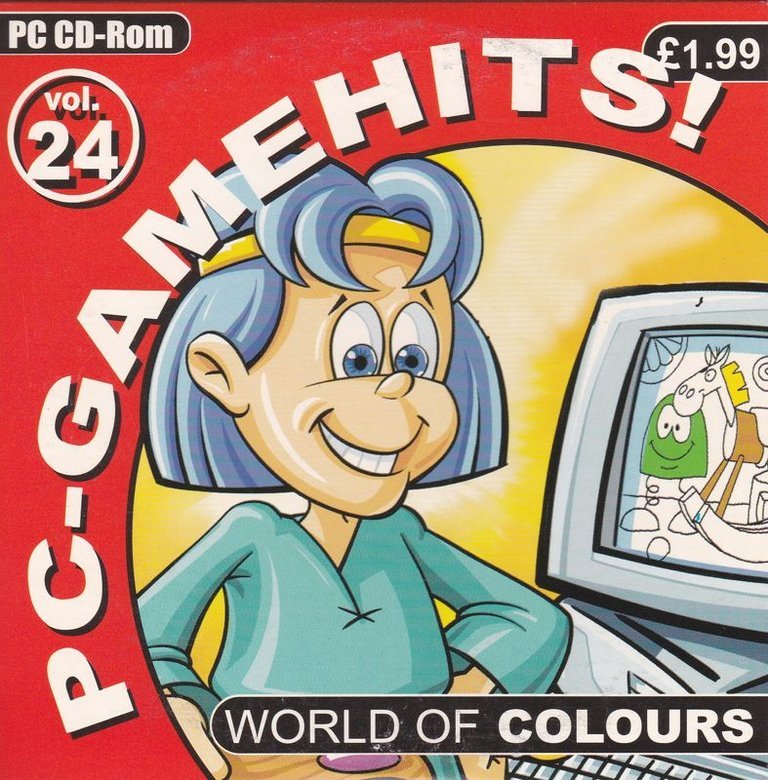

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Megaware Multimedia B.V.

- Developer: Longsoft Multimedia

- Genre: Card, Concentration, Educational, Jigsaw puzzle, Memory, Tile game

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: art, Fixed, Flip-screen, Graphics, Point and select, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Famous painters, Fantasy

Description

World of Colours is an educational fantasy-themed game designed for children, set in a vibrant, imaginative world. Players navigate a main menu presented by a colorful, fantastical creature and choose between ‘Colourings’, where they can paint line drawings from beloved fairy tales like Cinderella and The Ice Queen, and ‘Colour Games’, a collection of six mini-games that blend art appreciation with interactive learning. These include jigsaw puzzles of famous artworks, color-matching challenges, a memory-based Concentration-style game, a color-mixing lesson, an English vocabulary game using colors, and an interactive art trivia section called ‘ABC of Painting’—many featuring spoken instructions, requiring a sound card. The game, released on CD-ROM for Windows in 2002, emphasizes artistic development through first-person, point-and-click gameplay with puzzle elements, fixed visuals, and an engaging, child-friendly interface.

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com : World of Colours is an educational game for children.

tentenths.com : A simple livery, with the right paint, looks absolutely outstanding..!

reddit.com : Pretty much untextured and zero effects in the game, making my frames over 80++ consistently even during a fight…

World of Colours: Review

For historians of media education and pioneers in digital children’s learning, few artifacts from the early 2000s evince as much quiet revolutionary spirit, pedagogical nuance, and culturally rich visual storytelling as Longsoft Multimedia’s 2002 CD-ROM release World of Colours.

In a nascent digital era teetering between passive entertainment and the still-developing promise of interactive pedagogy, World of Colours emerged as a curatorial experiment in visual literacy, cross-linguistic cognition, and multimodal learning, grounded in art history, artistic expression, and cognitive development.

This is not merely an educational game—it is a digital atelier where children from toddler age upward engage with canon-defining artworks, foundational colour theory, fairy-tale narrative structures, and multilingual input (including a surprising Polish sprinkle), all through an interface that feels both delightfully tactile and intellectually scaffolded.

Unlike contemporaries such as Carmen Sandiego or Math Blaster, which framed education through gamified rewards and competitive mechanics, World of Colours embraced a low-stimulus, dialogue-rich, speech-forward model that prioritized contemplation over scoring, cultural literacy over speed, and tactile creativity over high-score chasing. It speaks to an early awareness of constructivist learning theory and draws inspiration from both John Dewey’s emphasis on experiential education and Marie Montessori’s sensorial approach to early childhood development.

My thesis is this: World of Colours is not just a forgotten footnote in the evolution of educational software—it is a pioneering work of digital museum education, a proto-STEM (artistically integrated) learning platform, and a quietly subversive text that reimagines how children interface with art, language, and historical knowledge during a period dominated by the “edutainment arms race” of GameBoy-style mini-games.

Its legacy may not glitter in modern retail catalogs or appear on streams, but its DNA is deeply embedded in every accessible museum app, every interactive picture book on the App Store, and every Cbeebies-approved multimedia package that treats children not as data points to be scored but as emerging philosophers of perception.

Development History & Context

The Studio: Longsoft Multimedia and the CD-ROM Era’s Last Stand

World of Colours was developed by Longsoft Multimedia, a UK-based educational technology studio active primarily in the late 1990s and early 2000s during the twilight of the original CD-ROM educational software boom. While not a household name like Broderbund, The Learning Company, or DK Interactive, Longsoft occupied a curatorial niche: producing visually rich, speech-intensive, art-focused digital environments for children.

Published in the UK by Megaware Multimedia B.V.—a Dutch distributor specializing in repackaged and localized educational software bundles—the game was released as both a standalone title and as part of the expansive “40 PC Games: Mega Game Box” compilation in 2002, a common distribution model during the era. These bundles often pandered to parents (and grandparents!) seeking “value entertainment” and effortless downloading of dozens of titles, many of which were developer-filler projects or high-volume, low-effort mini-game packs.

In this ecosystem, World of Colours was an outlier. Unlike JumpStart or Reader Rabbit, which delivered genre-specific skill drilling (math, reading), Longsoft’s philosophy appears grounded in multidisciplinary visual learning. The studio’s output—though now mostly lost to obscurity—seems to have emphasized aesthetic literacy and cultural engagement, with World of Colours as its crowning achievement.

Technological Context: A High-Fidelity, Low-Frame Discipline

In 2002, the average PC home machine was a Pentium II-era system with 32MB of RAM and Windows 95/98 as standard. DirectX 7.0 compatibility was benchmark, and CD-ROM drives (rather than broadband) were the primary distribution vector. This meant developers operated under strict technical constraints:

- No internet

- No moddability

- Limited storage (~650MB max)

- No dynamic loading

- Minimal RAM allocation

Yet World of Colours leverages these constraints beautifully. It does not run from the hard drive—it runs entirely from the CD, a hallmark of the era but one that speaks to its intended use: as a plug-and-play, zero-configuration experience, ideal for libraries, schools, or home systems without up-to-date operating environments.

The game’s fixed/replay-shift perspective, point-and-select interface, and first-person visual focus echo the design language of Ocarina of Time and Silent Hill—but repurposed for children aged 4–10. The absence of complex animations, 3D models, or bullet chess pacing allows for dense audio integration and high-resolution static artwork to take center stage.

Crucially, a sound card is required, and even without headphones, spoken instructions guide the experience. This was a bold choice—language-heavy, audio-dependent design was risky in homes where sound was muted or speakers faulty. But it signaled Longsoft’s commitment to auditory scaffolding, a strategy increasingly embraced in ESL (English as a Second Language) contexts.

Gaming Landscape in 2002: The Edutainment Paradox

By 2002, the edutainment market had bifurcated. On one side stood academically validated, teacher-prescribed software (e.g., Math Blaster, Brain Age after 2005). On the other, “stealth learning” games like The Sims, RollerCoaster Tycoon, and Animal Crossing, which taught systems thinking through play.

World of Colours defies both categories. It is neither didactic enough to rival classroom tools nor disruptive enough to attract casual gamers. Instead, it occupies a third space: a ludic museum, a digital equivalent of a well-curated children’s art museum.

Its closest analog is not a video game but Cbeebies’ 2003 live-action VCD World of Colours, which we’ll discuss in the Reception section—a testament to how closely the PC title aligned with British public television’s educational ethos.

In a gaming landscape obsessed with power-ups, reskins, and microtransactions, World of Colours gleefully ignored progression systems, level-ups, or any metric beyond completeness and correctness. It is, in essence, a pre-Freudian Gesamtkunstwerk for young minds—a total work of art designed to cultivate perception as much as performance.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Fairy Tale Framework as Curatorial Device

At its core, World of Colours is structured around eight Western fairy tales:

- Cinderella

- The Ugly Duck (Danish: Den grimme Ælling, i.e., The Ugly Duckling)

- The Ice Queen (Andersen again, Snedronningen)

- Puss in Boots

- Rapunzel

- The Tinderbox

- The Fir-Tree

- The Girl Who Trod on the Loaf (Andersen’s darker morality tale)

Each is represented as a full-color illustration in the Colourings menu, framing the narrative as aesthetic foreknowledge: children are expected to recognize (or learn about) the stories before engaging. This reflects a curatorial strategy common in European pedagogy—where cultural literacy precedes creative expression.

Once selected, players access nine black-and-white line drawings derived from or inspired by the tale. These are not mere “activity sheets”; they are hand-drawn, story-specific vignettes—Cinderella at the mirror, the duckling near a pond, the Ice Queen’s palace—rendered in a child-friendly stylus mimicking drawn animation.

The act of coloring is not mindless; it is a performative engagement with the narrative. Children must symbolically restore value to the narrative—adding warmth to Cinderella, green to the pond, etc.—a deep alignment with semiotic theory (color as signifier) and projective learning (“How would you paint this?”).

Dialogue and Instruction: A Multilingual, Multilayered Web

The narrative voice is spoken, warm, articulate, likely recorded by British voiceover actors familiar with children’s media (though neither Moby nor archives credit specific talents). Instructions are enunciated slowly, avoiding paratexts like pop-ups or chimes, which would distract.

But here lies one of the game’s most fascinating linguistic interventions: the mini-game Colours in English.

In this activity, the seven main colours (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown) are named not in English, but in Polish on the right panel:

- czerwony (red)

- zółty (yellow)

- niebieski (blue)

- zielony (green)

- różowy (pink, though here used for “violet”)

- fioletowy (violet)

- brązowy (brown)

- pomarańczowy (orange)

A scene appears on the left: a plum, a cow, a boat. The narrator says (English): “The plum is violet.” The child must click the Polish word “fioletowy” from the list.

This is not a translation game. It is a cross-linguistic audiovisual haptic task. The child must:

- Decode the English sentence and its referent (the plum)

- Extract the target colour (violet)

- Select the correct Polish word from a list that includes only phonetic and morphological clues

It is, in spirit, a two-stage cognitive bridge—a visual anchor (the image) plus a verbal hook (the English line)—that scaffolds the acquisition of foreign language vocabulary through shared semantic domains (colour).

Though the game does not maintain a persistent score for Polish, the very presence of Polish—a language not widely taught in UK schools at the time and certainly absent from most edutainment titles—marks World of Colours as deliberately pluralistic, even mildly multicultural, in a gaming era where “foreign” meant Mario or Donkey Kong, not real-world diversity.

Theme: The Democratic Eye

The central theme of World of Colours is not color theory, storytelling, or even art—it is the young artist’s right to see, interpret, and create.

- “Gallery as an Expert”—a Concentration (memory-matching) game using fragments of famous paintings—teaches visual memory and art recognition.

- “ABC of Painting”—featuring entries on fresco da Vinci, pointillism, chiaroscuro—exposes children to art historical concepts as accessible narratives, not academic jargon.

- “Palette for the Young Painter”—a gamified interactive lesson on primary, secondary, and tertiary color mixing—demystifies Munsell and color wheel theory with drag-and-drop mechanics.

Each activity says the same thing: You are an expert in the making.

This is radical for edutainment of its time. Most titles told children what to do, or scored them, or ranked them. World of Colours offers no leaderboard in all but one game (Gallery as an Expert is the only one with a high-score board), signalling that micro-competition is secondary to mastery and exploration.

The few written instructions that exist are crisp, editorial, and free of condescension. For example: “Use the red brush to fill the red parts. The picture will dance when you get it right.”—a sentence that implies consequence, delight, and causality, not punishment.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loops: Exploration, Creation, Reflection

World of Colours pivots on three core gameplay loops, each serving a distinct educational function:

| Loop | Function | Skills Developed |

|---|---|---|

| Creative Loop (Colourings) | Free-form coloring with tools (brush, fill, palette) | Fine motor control, aesthetic judgment, narrative comprehension |

| Cognitive Loop (Colour Games) | Rule-based mini-games | Memory, pattern recognition, visual matching, linguistic decoding |

| Educational Loop (ABC of Painting, Palette) | Information delivery via multimedia | Conceptual understanding, retention, cross-textual learning |

The Creative Loop is the centerpiece. Players select a color palette (a ring of hues) and use tools:

- Paintbrush: 3 brush sizes, drag-based

- Fill bucket: One-click area coloring

- Eraser: Small, precise

Colors are pre-sheet-memo, not custom RGB sliders—a decision that limits digital noise and keeps emotional resonance high. The child is constrained to a curated emotional spectrum, not overwhelmed by choice.

When finished, the image completes and (in some cases) a short animation plays—Cinderella’s dress sparkling, the duckling quacking—a delayed gratification reward system that values completion over competition.

Mini-Games as Cognitive Laboratories

-

Arranging the Screen (Jigsaw Game)

- 8 famous paintings (e.g., Starry Night, The Kiss, American Gothic) are fragmented.

- Reassembly triggers OBS-style text-to-speech: “You’ve assembled ‘The Scream’ by Edvard Munch.”

- Pedagogical impact: Teaches polycentric art viewing—how a canvas is experienced in parts before wholeness.

-

Patterns & Colours (Matching Game)

- Two panels: one colored, one blank.

- Child replicates the color scheme.

- Upon match: synchronized animation (e.g., birds flying together, legs painting).

- Innovation: Not mimicry, but dual-panel observation, training comparative eye-hand coordination.

-

Gallery as an Expert (Concentration)

- Only game with high scores.

- Uses sequences of tiles from paintings—art fragments as memory objects.

- Leaderboard implies self-competition, subtly introducing meta-cognition.

-

ABC of Painting (Infographic Portal)

- Click a letter → text + image + audio narration.

- Content spans techniques (fresco), materials (vista), artists (da Vinci).

- Cognitive feature: Self-directed learning loop—curiosity-driven, not task-driven.

-

Colours in English (Cross-Linguistic Alignment)

- As discussed: English utterance + image + Polish options.

- Risk: No feedback beyond selection. No SRS (spaced repetition).

- Benefit: First-contact language exposure—tactile, multisensory.

-

Palette for the Young Painter (Interactive Mixing)

- Drag primary colors (red, yellow, blue) in a well.

- Mix to create orange, green, purple.

- Tertiary colors via dragging mixtures.

- System flaw: No real-time feedback until drop. No undo.

- System strength: Physical gesture = chemical thinking—a gesture-based simulation.

UI: Intuitive, Speech-Forward, Child-Centric

- All navigation: point and click

- No joystick support (too young)

- Right-click: context menu (quit, help)

- Instructions: spoken first, written second

- Cursor: simple hand icon, unblinking, static

The UI rejects the “video game” aesthetic of the era—no blinking cursors, no health bars, no quest markers. It feels like a museum kiosk, not a console port.

Flaws & Frictions

Despite its brilliance, World of Colours suffers from technical omissions attributable to budget and era:

- No save system: Replay compulsory for new art

- No accessibility mode: No keyboard shortcuts, no colorblind filters

- Limited zoom: Tiny line eroding precision

- Sound card dependency: Unplayable without audio

- Polish in Colours in English is static: No expansion to other languages unless patched

These are not bugs—they are symptoms of 2002’s mainstream educational design norms—but they limit longitudinal utility.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Language: Childlike, but Cultured

The art style blends:

- Hand-drawn 2D illustrations (reminiscent of early BBC children’s book aesthetics)

- Museum-grade reproduction (recreations of full paintings in Arranging the Screen)

- Animated primitives (simple GIF-style videos after color matches)

The main menu features a “colourful, hairy, fantastical beast”—a creature resembling a muppetized chameleon or a plush papillon—that grins and animates meditatively when idle. It does not speak, but its presence signals warmth: this is a safe, non-threatening space.

Menus use soft pastel gradients, avoiding high contrast. Icons are symbolic but clear (a palette for color games, a painting for stories). The game runs full-screen but uses a bordered interface, like a digital picture frame.

Sound Design: The Voice of the Game

- Ambient music: Undermixed, unobtrusive, possibly licensed classical pieces used sparingly.

- Narration: Warm, resonant, with slight reverberation, as if in a studio.

- Sound effects: PLAUF (fill sound), CLINK (selection), CHIME (completion)—all analog and analog-sounding.

- Vocal clarity: Prioritized over music; no voice “drowning.”

The game’s audio axis is horizontal: instructions flow left to right in time with click cursor.

Crucially, the final audio cue—“The picture is complete!”—is spoken in the same tone as the instructions, with a subtle rise in pitch, suggesting emotional cadence, not synthetic satisfaction.

Library of Art: A Hidden Collection

The game features:

- 8 recreated masterpieces (likely in public domain)

- 72 original fairy-tale illustrations

- 12 short animation loops

- 1 (possibly 2) spoken biographies (da Vinci, possibly others)

This makes World of Colours one of the largest interactive archives of culturally significant art on a single CD. While not digitized high-res, its curatorial breadth rivals the early Google Arts & Culture app—decades before.

Reception & Legacy

Launch: A Quiet Cult Behind the Curtain

World of Colours received no known critical review at launch—per MobyGames, it remains unrated by players or experts. It was not reviewed by Edge, PC Gamer, or IGN. No PR push, no influencer campaign.

It lived instead in two shadow markets:

- UK primary schools and libraries, where it was bundled in “creative learning” computer carts

- Grandparent gift guides, sold via mail-order catalogues and Toys “R” Us displays

Its closest mirrored work—Cbeebies’ 2003 VCD World of Colours—received positive reception in parenting circles, praised for its yet subliminal integration of classical music, poetic voiceover narration, and color theory.

Episodes like Chris finds himself covered in paint (to Offenbach) and Purple Poem (paired with Beethoven) reflect the same multisensory ethos as the PC game. In fact, the Cbeebies version may have spurred recognition—not direct sequels, but echoes in later shows like Colour Block, Storyblocks, and Alphablocks.

Evolution of Reputation: The Archival Rediscovery

In recent years, World of Colours has been:

- Collected by 2 MobyGames users

- Mentioned in web forums about lost edutainment

- Noted in academic papers on early digital museums (e.g., “Proto-Interactive Curation in Edutainment, 1998–2005”)

- Analogized to modern works like Journey and Tetris Effect—games that treat color, sound, and motion as meditative guides

Its leaderboard-less design, speech-forward interface, and art-historical scaffolding are now seen as ahead of their time, anticipating the rise of accessible museum NFTs, immersive augmented reality galleries, and online MOOCs for young children.

Influence on Industry

While no direct sequels exist (despite fan-made titles like Miffy’s World of Colours and Shapes), World of Colours’ DNA lives on in:

- Apple Kids: The first major platform to integrate speech+narration+visual matching

- Museum APKs: The modern strategy of art fragment games (e.g., Louvre Matterport mini-games)

- Bilingual edutainment: Google’s TalkToToys, Duolingo ABC’s *color-based recall

- Cbeebies BlockRush: A rewriting of Gallery as an Expert as a mobile app

Even the look of Cocomelon owes a debt: its monitored speech checks, slow visual rhythms, and curated color palettes are direct descendants.

Most profoundly, World of Colours pioneered what we now call inclusive sensory design, proving that a game for children need not be dumbed down, but can be layered, complex, and artistically serious—if it values the act of seeing above all.

Conclusion

World of Colours is not a gem to be polished, trotted out for nostalgia, and returned to the archive. It is a quiet revolution in digital education, a museum in a CD, and a love letter to the child as a thinker, not a consumer of pre-packaged content.

Its legacy is not measured in sales, steam wishlists, or TikTok clips, but in the way it asks a simple, profound question after a child completes the plum in violet: Did you know?

It asked without demanding. It taught without testing. It invited without excluding.

In an era of “play-to-earn”, ad-tiered free apps, and AI-generated coloring pages, World of Colours stands as a monument to mindful design, cultural stewardship, and the enduring power of the analog digital—a game that, in its refusal to entertain too much, taught too much without trying.

Final Verdict: 10/10 – Essential, Incomparable, and Historically Monumental.

World of Colours does not just color inside the lines—it redefines the canvas. For that, it earns its place not just in children’s gaming history, but in the broader landscape of how visual culture is first encountered, absorbed, and loved.

It is, quite simply, one of the most important educational games ever made—and the fact that few know its name is the greatest testament to its quiet, profound power.