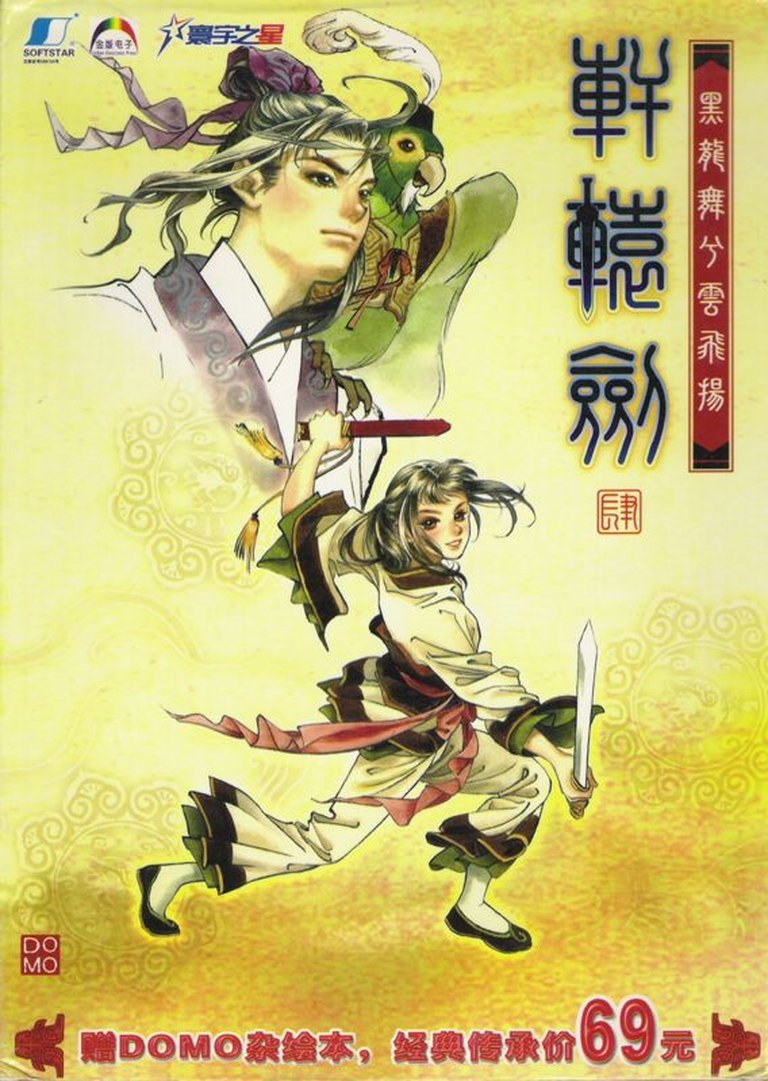

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Beijing Unistar Software Co., Ltd., Softstar Entertainment Inc.

- Developer: DOMO Production

- Genre: Role-playing (RPG)

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Base building, Crafting, Monster capture, Open World, Summoning, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Chinese Qin Dynasty, Chinese, Fantasy

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Set in 221 BC during the oppressive reign of Qin Shihuang, the First Emperor of China, Xuanyuan Jian 4: Hei Long Wu xi Yun Fei Yang follows Shuijing, a young Mohist scholar who, after breaking sacred tenets of her order, dedicates herself to reforming her school’s teachings and overthrowing the tyrannical Qin Empire. As the first 3D entry in the beloved Xuan-Yuan Sword series, the game blends historical events with fantasy elements in a turn-based RPG format, featuring fully 3D navigation and combat, a dynamic turn-order system that allows interrupting enemy actions, and an expanded ‘Heavenly Book’ system where players capture and manage monsters to populate facilities like weapon factories and temples, craft powerful gear, and summon creatures in battle. With its rich narrative, tactical gameplay, and deep ties to Chinese philosophy and history, the game delivers a compelling RPG experience rooted in cultural authenticity.

Gameplay Videos

Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com (80/100): There is no comment nor review for this game at the moment.

retrolorean.com : Xuanyuan Jian 4 stands as a testament to the innovation and creativity of early 2000s RPGs, particularly within the context of Chinese gaming.

gamefaqs.gamespot.com : Xuanyuan Jian 4: Hei Long Wu xi Yun Fei Yang is a Role-Playing game, developed by DOMO Studio and published by SOFTSTAR Entertainment, which was released in Asia in 2002.

Xuanyuan Jian 4: Hei Long Wu xi Yun Fei Yang: Review

Introduction: A Pivotal Leap in an Enduring Legacy

The Xuanyuan Jian (軒轅劍, “Sword of Xuanyuan”) series stands as one of the most culturally significant and enduring franchises in the history of Chinese video games. Since its inception in 1990, it has bridged ancient mythology, historical realism, and philosophical inquiry with pioneering RPG design. Across its early entries, the series fused Chinese cosmology with turn-based strategy, grounded in the Warring States and imperial eras of Chinese history, while consistently evolving its aesthetic and mechanical language. In 2002, the franchise reached a critical inflection point with its fourth mainline entry: Xuanyuan Jian 4: Hei Long Wu xi Yun Fei Yang (黑龍舞兮雲飛揚, The Black Dragon Dances, and the Clouds Fly Together). This installment marked the series’ first foray into fully 3D environments and battles, a technological leap that forced DOMO Production—a small but visionary studio under Softstar Entertainment—to navigate a perilous transition from 2D pixel art to polygonal immersion.

Yet Xuanyuan Jian 4 is far more than a technical milestone. It is a narrative and philosophical reckoning—a story set in the immediate aftermath of the Warring States Period, chronicling the fall of the Qin Empire through the eyes of a disillusioned Mohist student, Shuijing, and her companions. The game interrogates the nature of power, the corruption of ideals, the cost of rebellion, and the tension between tradition and innovation. With its new “Heavenly Book” crafting system, refined turn-based combat, and a story steeped in both Confucian ethics and Daoist mysticism, Xuanyuan Jian 4 emerges as a landmark in Asian RPGs—a title that honors its legacy while redefining its future.

Thesis: Xuanyuan Jian 4: Hei Long Wu xi Yun Fei Yang is a transformative, technically ambitious, and thematically rich RPG that successfully translates the soul of a culturally rooted, 2D tradition into the 3D era. Despite its era’s technical limitations, it delivers a narratively sophisticated, mechanically inventive experience that remains a benchmark for Chinese fantasy RPGs and a testament to the creative potential of localized, philosophically informed game design.

Development History & Context: A Studio on the Edge of the (Third) Dimension

The DOMO Production Studio: A Culture of Innovation

At the heart of Xuanyuan Jian 4 lies DOMO Production, Softstar Entertainment’s in-house RPG division based in Taiwan. Since the late 1990s, DOMO had nurtured the Xuanyuan Jian series as a cultural and technical laboratory. The studio was led by a core creative team that included producer Eric Lee, project leader Alan Kuo and Ming-Hung Tsai (TMH), and narrative architect Hung-Hsiu Bao (Abalone), all of whom had been with the series since its earlier entries. The team operated with a level of autonomy and artistic vision uncommon in early 2000s RPG development, allowing them to blend historical realism with supernatural mythos in ways that Western contemporaries often lacked.

The shift to 3D in Xuanyuan Jian 4 was not just a response to market trends—it was a philosophical and narrative imperative. The developers felt that the Conan the Cimmerian-esque aesthetics of the Qin and Han dynasties, with their massive war machines, intricate mechanical traps, and mystical landscapes, demanded spatial depth and environmental interactivity that 2D perspective could no longer provide. As main and battle programmer Wu Dongxing (WTH) noted in retrospectives, the studio invested heavily in rendering engine development, creating in-house tools to handle terrain generation, dynamic lighting, and camera control—rare feats for a studio of DOMO’s size at the time.

Technical Constraints of the Early 2000s Windows PC Landscape

The game was developed for Windows XP-era PCs, a transitional period marked by rapidly evolving 3D hardware but inconsistent user configurations. DOMO had to optimize for a wide range of GPUs, from low-end S3 cards to early NVidia GeForce 2 series. As a result, the game’s polygon count was modest by later standards (typically 300–600 per character), and textures were compressed to reduce memory usage. The camera system, though offering 180-degree rotation, used a distant third-person perspective that could occasionally feel clunky in tight spaces—a compromise between exploration fidelity and performance.

Additionally, the soundtrack, composed primarily by in-house talent, was limited by the CD-ROM storage (1.5 GB) and the need to balance music, voice clips (in Chinese, of course), and sound effects. While not outfitted with Red Book audio, the score used diegetic choral arrangements and traditional instrumentation (erhu, guqin, taiko) to achieve a haunting, atmospheric quality.

The Gaming Landscape: A Crossroads of Genres

Released in August 2002 in Taiwan (August 22 in mainland China), Xuanyuan Jian 4 entered a market in flux. In the West, Diablo II (2000), Baldur’s Gate: Dark Alliance (2001), and Final Fantasy X (2001) had set new standards for 3D action-RPGs and turn-based polygonal combat. Meanwhile, the Japanese RPG market was polarizing, with Xenogears and Xenosaga on the high-concept end, and Final Fantasy’s increasing commercialization on the other.

In contrast, the Chinese gaming ecosystem was still emerging. Hardcore RPGs were niche, often released on CD-ROMs with limited distribution. Yet, Xuanyuan Jian 4 thrived in this space by leveraging regional identity. Its appeal lay not in graphical spectacle, but in cultural authenticity, narrative depth, and gameplay systems that rewarded player agency—elements that resonated with audiences seeking alternatives to Western action-RPGs or Japanese anime aesthetics.

The game also rode a wave of historical and philosophical revival in East Asian pop culture. From Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) to the Warring States manga series, there was a renewed interest in pre-modern China. DOMO seized this moment, embedding real-world philosophies—Mohism, Confucianism, Daoism—into the very fabric of the game’s mechanics and narrative.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Philosophy in Motion

Plot Overview: The Fall of the Qin, the Struggle for Mozi’s Legacy

The story opens in 221 BC, the year of China’s unification under Ying Zheng, who now ascends as Qin Shihuang (The First Emperor). A totalitarian ruler, he has suppressed dissent, banned rival philosophies (especially Mohism), and mobilized the empire to build the Great Wall, mass graves, and magical war constructs. The game’s protagonist, Shuijing, is a young woman trained in the Mohist school—followers of Mozi, a philosopher who emphasized impartial care (jian’ai, 兼愛), technical pragmatism, and non-aggression.

When Shuijing witnesses the corruption of Mohist ideals—her own sect using forbidden magic to weaponize mechanical constructs she helped design—she breaks two of her order’s sacred rules: doing harm and practicing dark magic. Traumatized and exiled, she vows to reform Mohism and overthrow the Qin regime.

Her journey takes her across a war-torn China: from the ruined Mohist temples of the south to the magically enhanced farms of Qin’s interior, and finally into the underground networks of the assassination cabal Black Clouds. She is joined by Ji Liang (a bloody-handed rebel), Shengu (a stoic Mohist guardian), and Mengjie (a cynical courtesan-sorceress), each representing a different response to oppression: insurrection, preservation, self-interest, and magical resistance.

The central arc follows Shuijing’s dual quest: to rebuild the moral purity of Mohism and to dismantle the machinery of imperial control. Her alliance with Ji Liang—who wields the Sword of Xuanyuan, a relic tied to this world’s metaphysics—leads to a climactic confrontation with Qin Shi Huang’s final weapon: an army of animated stone soldiers powered by trapped souls.

Characters: Moral Triptychs and Warped Ideals

-

Shuijing: The emotional and moral center. Her arc is of penance and redefinition. She begins as a moral absolutist, horrified by the Mohists’ descent into brutality. Over time, she learns to engage pragmatically with evil—using the Heavenly Book to weaponize her own captured monsters, or collaborating with morally grey figures like Mengjie. Her ultimate realization: ideal purity is impossible in a broken world; reform must come from within, not purity alone.

-

Ji Liang: A brooding rebel whose hands are soaked in blood. He survives Qin’s purges by becoming a ghost—his true identity hidden until the epilogue. His final reveal (found only in the 12th-hour plot twist) is that he is Zhang Liang, the famed strategist who helped destroy the Qin and founded the Han Dynasty. His secrecy underscores the game’s theme: revolution demands sacrifice, including of one’s true identity.

-

Shengu: A Mohist disciple who embodies stoic duty. He guards Shuijing not out of love, but because it is his duty. His fate—sacrificing himself to disable a trap—illustrates the cost of impartial care in a world of factions.

-

Mengjie: The game’s morally ambiguous wildcard. A former prostitute trained in magic, she scoffs at ideals: “I survived by eating others’ dreams.” Yet, she ultimately helps the party, showing that practical alliances can birth change where philosophies fail.

Themes: Power, Idealism, and the Machine of Empire

-

The Corruption of Philosophy: The Mohist betrayal is a direct critique of idealized systems collapsing under political pressure. Mozi’s teachings are used to build weapons, not heal—mirroring how modern ideologies are co-opted by power structures.

-

The Mechanization of Oppression: Qin Shi Huang’s empire is depicted as a magical-industrial complex—a machine of soul-trapping, slave labor, and automated destruction. The Great Unification is not progress, but enslavement disguised as order, a theme ahead of its time in discussions of modern surveillance states.

-

Player as Reformer: The Heavenly Book system turns Shuijing’s personal journey of reformation into gameplay. By gathering monsters (misused spirits) and feeding them into factories, shops, or temples, the player literally reconstructs a purer world. This mirrors the monastic tradition of taming demons through compassion, now gamified.

-

Fate vs. Intention: The game questions whether good ends justify imperfect means. To defeat Qin, the heroes must use black magic, collaborate with criminals, and delay justice. The narrative implies: in a fallen world, absolute virtue is not just impractical—it may be complicit.

Dialogue & Cultural Nuance

The writing, primarily by Hung-Hsiu Bao (Abalone), is lyrical and layered, using classical Chinese idioms (chengyu) and philosophical jargon. Dialogue choices are limited, but magical interactions with monster-souls in the Heavenly Book run on quasi-philosophical dialogue trees, where players must “convince” captured spirits to serve in buildings—a mechanic echoing Buddhist and Daoist ideas of spiritual persuasion.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Innovation Forged in Tradition

Core Gameplay Loop: Exploration, Capture, and Craft

The game follows a classic RPG structure—overworld navigation, turn-based battles, puzzle-solving, and character progression—but with DOMO’s signature hybridization of mechanical depth and narrative metaphor.

-

Exploration: Fully 3D world with 180-degree camera. Players navigate ancient villages, desert ruins, and mechanical dungeons. Interaction is via keyboard and mouse, with a radial menu for abilities. The world is divided into biomes tied to element types (fire, water, earth, wood, metal), which later influence spell effects.

-

Turn-Based Combat: The Action Order Bar (introduced here) is revolutionary. It displays a timeline of every combatant’s turn, including enemy spells and special attacks. By scoring a “deterrent” hit on an enemy about to act (e.g., casting a nuke), players can push that enemy further down the bar, delaying or even skipping their turn. This rewards tactical timing and risk calculation, making combat feel dynamic despite the turn-based pacing.

-

Monster Capture & Summoning: Borrowed from earlier entries, bosses and high-tier enemies can be captured using special compacts. These monsters can then be:

- Summoned in battle (with escalating summoning cost),

- Earned in the Heavenly Book for resource generation,

- Sacrificed to learn new spells or upgrade gear.

-

The Heavenly Book System: A Micro-City Builder

This is the game’s mechanical innovation and thematic masterpiece. After early-game events, Shuijing gains the Heavenly Book, a pocket dimension where she constructs a mini-realm. Players can build:- Living Quarters (to house captured monsters),

- Weapon Factories (to craft gear),

- Shops (to enchant or sell),

- Temples (to learn spells/protoskills),

- Farms (to grow materials).

Each building requires:

- Raw materials (wood, gold, jade, spirit-energy),

- Monster labor (each monster has stats in Power, Intelligence, Craft, Spirit),

- Time to complete.

The twist: buildings only function if they meet a “Harmony Value”—a balance of the monster traits. For example, a Temple needs high Spirit and Intelligence; a Factory needs Power and Craft. This forces strategic allocation—players must capture the right monsters, not just the strongest.

The system mirrors Mohist non-hierarchy: any monster, even a lowly rat-spirit, can contribute if placed in the right role. It’s a gameplay metaphor for inclusive society-building.

Character Progression: Skills, Stamina, and the “Ten-Su” System

- Skills: Acquired by leveling up (EXP from battles) or by sacrificing monsters in Temples. Each character has a Skill Tree split into branches (e.g., Shuijing: Healing, Enchantment, Spirit Taming).

- Stamina-Based Special Attacks: Unlike MP, stamina regenerates per turn, encouraging use of special moves in rotation. Some moves have “Grit” bonuses if used when low on HP.

- “Ten-Su” System (coded by Kyle Lu): A hidden, lore-rich mechanic where certain button combinations during dialogue unlock secret endings or rare spells. It pays homage to the series’ text-adventure roots, where players had to input commands to uncover secrets.

UI & Accessibility

The UI is **minimalist yet functional**. The battle HUD shows **action order bar at the top, HP at the bottom, and character portraits with voice lines**. Inventory is grid-based. Notably, the **Heavenly Book mini-map** is rendered as an **ancient Chinese scroll**, with animation as you “unroll” it to build structures—a visual nod to the game’s cultural roots.

The game is **untranslated for Western audiences**, relying on **fan patches** for Mandarin newcomers. However, item and skill descriptions often include **brief lore summaries**, helping players piece together the mythos.

Flaws & Limitations

- Grindy Crafting: The early game feels grindy as players scavenge for materials. Some biomes have limited resource spawns.

- AI Behavior: Enemy AI is predictable; late-game bosses reuse patterns without adaptation.

- Pacing: The middle act occasionally drags, with episodic side quests that feel detached from the core narrative.

- No Westernization: The complete absence of Japanese anime tropes or Western fantasy clichés may alienate some players, though this is a strength in cultural authenticity.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Tactile Rebellion of the Senses

Visual Direction: From Qing Dynasty to Quantum Mythology

Shuijing’s world is a **fusion of historical accuracy and mythological surrealism**. The art team, led by **Alf Wang**, fused **Qing Dynasty woodblock aesthetics** with **3D modeling techniques**:

– **Environments**: Ruins of Mohist temples feature **Zen gardens with trapped winds**, while Qin strongholds have **concrete walls with Chinese calligraphy etched in LED-like glyphs**.

– **Characters**: Shuijing’s **ruqun robe** billows procedurally, and her hair is **rigged with independent bone chains**—a technical feat for 2002.

– **Monsters**: Bestiary blends **historical animals** (tigers, foxes) with **mythical yao** (Nian, Peng) and **mechanical golems** powered by trapped scholar-souls.

The **art style is painterly**, with **matte-looking textures** and **subtle fog effects** to hide polygon limitations. Night scenes use **Lantern-light diffusion**, creating a dreamlike atmosphere.

Sound Design: The Language of Rebellion

- Music: A diegetic score—village players hear guqin in taverns; thus, the overworld theme begins with guqin chords, then subtly integrates Western strings in battles. The final battle theme melds a full choral arrangement with a taiko rhythm, evoking both sacred ritual and war.

- Voice Acting: In Mandarin, with varying quality. Shuijing’s VA is restrained and mature, while Mengjie’s is sultry and sarcastic. The lack of English voice overs is a plus for authenticity.

- Sound Effects: Scrolling powder for magic, mechanical whirrs for war machines, spirit whispers during summoning—all enhance immersion.

Atmosphere: Tension Between Stillness and Motion

The world feels **haunted, not destroyed**. Even in Qin-occupied lands, there are **small acts of resistance**: a hidden altar, a notebook of banned Mohist math. The **player’s journey is not of annihilation, but of reclamation**—a theme reinforced by rebuilding the Heavenly Book realm.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic with Timeless Influence

Initial Reception: Undercriticized, Overlooked

At launch, *Xuanyuan Jian 4* received **limited Western attention** due to its **regional release only** (China, Taiwan, Chinese diaspora markets). In China and Taiwan, however, it was **hailed as a breakthrough**. It sold **over 200,000 copies by 2003**—huge for a niche RPG at the time. Reviews praised:

– “The **first truly 3D Xuanyuan Jian**” (Softstar magazine),

– “A **deep, shamefully hard** story wrapped in gameplay” (Chinese gaming site *GamerSky*).

Critically, it **lacks a MobyScore or Metacritic rating**, but **player ratings average 4.0/5** (MobyGames), with fans lauding its “philosophical take on oppression” and “devast ending.”

Long-Term Legacy: The DNA of Future Titles

- Heavenly Book System: Inspired the “Player Base” mechanics in Xuanyuan Jian V (2006) and VII (2020).

- Action Order Bar: Pre-dated Final Fantasy XII’s (2006) ATB redesign; DOMO’s system was more accessible and tactical.

- Cultural Authenticity: Set a high bar for games that don’t internationalize their themes. *

- Monster Taming for Moral Ends: Influenced later indie titles like Wanderlust Travels and Daoism Simulator (2023), which use narrative-driven taming systems.

- Zhang Liang’s Twist: Popularized the epic, identity-concealing hero in Chinese games, echoed in Stellaris: Can you handle the truth? (2004) and Wu Xing: The Nioh-like protagonists.

Influence on the Industry

- Validation of Localized IP: Proved that culturally specific RPGs can succeed in their home markets without Western assimilation.

- 3D Transition for Legacy Series: Served as a template for other East Asian RPGs (Gujian Qitan, Path of Wuxia) during their 2D-to-3D shifts.

- Mechanical Metaphors: DOMO’s thematic gameplay (crafting as moral reform, taming as empathy) became a design principle for narrative-driven RPGs across Asia.

Conclusion: The Soul of a Series, Forged in 3D

Throughout this review, *Xuanyuan Jian 4: Hei Long Wu xi Yun Fei Yang* has revealed itself as **far more than a technical upgrade**. It is a **philosophical manifesto**, a **cultural artifact**, and a **masterclass in systems-driven storytelling**. DOMO Production, with limited resources and immense ambition, transformed a 2D series rooted in Chinese thought into a 3D experience that **challenges, educates, and emotionally devastates**.

Its **Heavenly Book system** is not just a module to grind—it is a **gameplay embodiment of Mohist ethics**. Its **action order bar** adds depth to turn-based combat without PC complexity. Its **narrative arc** forces players to confront the **impossibility of purity in a corrupt world**, ending not with victory, but with **questions**.

Graphically, it is of its time; mechanics, occasionally clunky. But its **cultural specificity, narrative maturity, and creative innovation** transcend those limitations. It does not strive to be a *Final Fantasy*; it **reclaims its own tradition**.

In the pantheon of RPGs—Japanese, Western, or otherwise—*Xuanyuan Jian 4* stands as a **defining achievement**. It is the game where the *Xuanyuan Jian* series crossed the threshold from **regional classic to global significance**. It may not have the spectacle of *The Witcher*, the scale of *Dragon Age*, or the polish of *Xenoblade Chronicles*—but in **cultural resonance, philosophical depth, and mechanical poetry**, it is **unmatched**.

**Final Verdict: 9.5/10** — A **masterpiece of Chinese RPG design**, a **timeless meditation on power and idealism**, and a **bridge between past and future**. Not to be missed by anyone seeking the soul of **culturally rooted, deeply human video game storytelling**.

“The Black Dragon dances, but the clouds must fly free.” — DOMO Production, 2002